76 Hamilton Place, (originally no.27)—built in 1833 to house five respectable households: three in the stair, one in the main-door flat and one in the basement.

Former residents include:

1941—Jeannie Carstairs, a 58-year-old woman, divorced, who started a summer job as a maid at the Trossachs Hotel near Callander on a Friday and died around 5 o’clock the next morning in a fire that consumed the garage that served as the seasonal staff’s sleeping quarters.

1926—Johanna Murray, the wife of a Stockbridge baker, who always carried in her handbag the last letter her son Willie had sent her, written in 1918, in Baghdad, where he’d been an artilleryman and had died in an accident two days after writing it. He was twenty-seven years old.

His regiment sent Johanna a tiger skin rug that Willie had bought, which she kept in her lobby, where it later became an exotic object of fascination for her grandchildren, their fingers tracing the edges of the bullet hole in its forehead.

Another of her sons, Tom, also died in the war—at the age of twenty, in the battle of Neuve Chapelle, a three-day offensive in 1915 in which twenty thousand men died with, according to historians, “no strategic effect”.

A friend of Tom’s, home from the front, visited Johanna and gave her Tom’s identity disc. Another treasure, like the letter and the tiger skin rug.

Tom’s number was stamped on the disc: 6320. A minor family sensation was caused when Johanna’s sister confided that she recognised the number, which, she said, had some months previously appeared repeatedly in terrible dreams that had kept her from sleeping.

A third son, John, survived the war and was employed for some decades as the doorman at the General Post Office. He would have been known by sight to virtually everyone in the city.

Johanna spent her final years living with her daughter’s family, mostly sitting at their front window. In the evenings, she would relate her observations, such as, “235 people have passed along East London Street this afternoon.” She died in 1943, at the age of 84.

1924—David Bookless Gray, a 76-year-old retired wine and spirit merchant, who fell off an electric tramcar in Frederick Street one Saturday afternoon and, suffering a bad concussion, was taken to the infirmary, where he contracted pneumonia and died ten days later.

1918—Helen Kerr, the widow of a Leith customs officer, whose only son, Alick, was an office clerk in an artillery regiment, filling out forms, filing documents and performing other non-combat functions. Nevertheless, he was killed during the German spring offensive, aged 25.

1901—Edward Nightingale, who, in the first half of the previous century, had been a clothier with a shop in South St Andrew Street and a fine home in Rutland Square, and had no trouble turning a profit until 1851, when he got married to the daughter of a well-to-do gentleman.

He fell into litigation with his wife’s family over his share of a trust fund left by her father when he died. Ruinous lawyers’ fees and judgments going against him caused him “to become so unhinged” he “was no longer fit to carry on his business”, so he sold it to his brother.

When his wife died, his sister came to keep house and look after the children. He paid her £30 a year but, with no income, soon owed her more than he could pay. His house and furniture was signed over to her, his name taken off the bell pull.

He and his children became his sister’s lodgers in what had formerly been his house and, eventually, after his children were grown, he moved down to Hamilton Place, where he remained until he died at the age of 89, of general debility.

1889—Thomas Cooper, a 32-year-old dentist, who fell off his tricycle while cycling up a hill in Blackhall. He struck his head on the ground, causing a brain bleed that no one knew about or even suspected until four days later, when he suddenly collapsed, dying later that evening.

1888—James Cooper, who had received an MA from Cambridge University in his youth, and spent his retirement tutoring students for their preliminary exams, advertising his “long and very successful experience.” He died aged 76, four months before his son, Thomas (above).

1886—William Stone, a law clerk, whose children all died before they grew up. The last to die, Nora, was poorly from infancy and wasted away for a year before succumbing to pneumonia in the spring of her third year.

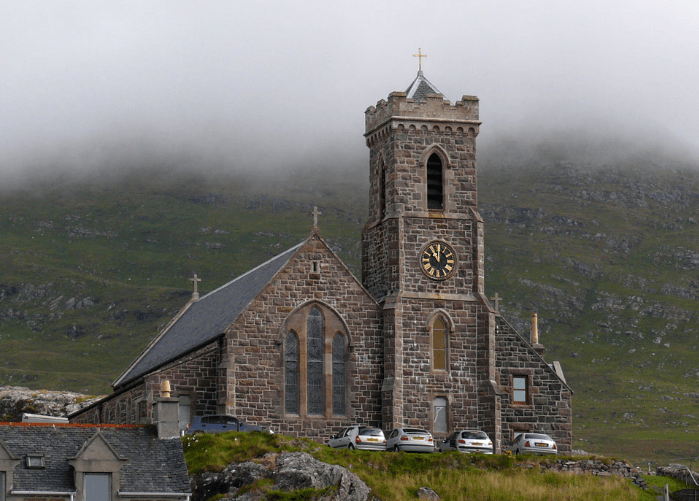

1872—John Rutherford Wright, who lived in the main-door flat and was a landscape painter, sculptor and architect of schools, hospitals, churches and other public works across Scotland.

In 1909, when he was eighty, he was sued by Harold Hill, a lithographer, whose eight-year-old son was at the edge of a crowd of people watching the cleansing department hose the street when he was jostled against the tenement’s railings, one of which was missing.

The boy fell through the gap to the basement area below, sustaining injuries for which Harold sought £250 recompense. Pointing out that he was not entirely to blame, as he was not the sole owner of the tenement’s railings, John offered £55, which Harold accepted.

A close examination of the railings in June 2023 revealed none missing.

1865—Mr Bennett, who borrowed a copy of Nicholas Nickleby from Mr Porters’ circulating library on Howe Street and failed to return it. The library made inquiries at the tenement only to find that he had left his flat, taking with him all his possessions, and their book.

1847—Peter McLay, a grocer, whose son Walter died at the age of six. His daughter Mary, born with a weak heart, was four at the time. She never thrived, suffered from dropsy all her life, and died in 1861, aged eighteen. Peter sold the flat the very next month.

(The McLays lived (and died) in the top floor flat, whose current resident kindly invited me into the stair and back green to look around when he noticed me taking an unusual interest in his property.)

The tenement was built on the grounds of the old mansion of Patriot Hall, with its “stable, hayloft, poultry yard, kitchen garden and park with fine wall-fruit, espaliers and shade trees”, which survived a few decades more, its grounds gradually sold off for housing until it, too, was lost.

It was replaced by the Patriot Hall Buildings, “43 Houses for the Working Classes, with the advantage of a large drying green.” The building remains, but the working classes seem to have gone, and the green has been tarmacked over to provide parking for nine private cars.

Excellent reading you never fail to entertain !

LikeLike

Thanks very much!

LikeLike