21 East Crosscauseway, built around 1778—almost 250 years ago—on what is now a side street but was then the only paved road in the south of Edinburgh, which linked the city’s two main roads south. (The name comes from an unfortunate anglicisation of the Scots word “causey”, meaning “paved”.) There are currently 10 flats in the stair; who knows how many originally.

Former residents include:

1987—Joy Wilson, 22 (below, centre), a pharmacist, who left her flat before sunrise on May 1, and walked with her friends from St Mary’s Street through the pouring rain to the slopes of Arthur’s Seat, where they joined an unusually low turn-out of around 300 people for the May Day dawn pilgrimage.

One of the women said, “I whole-heartedly believe in the legend about May Day dew making you beautiful—that’s why we are here.” Another said the conditions were awful: “This is my first and last dawn trip up Arthur’s Seat. I didn’t expect it to bucket with rain.”

1963—William Beveridge, who was in Ramsay colliery, Loanhead, filling tubs with coal as it accumulated in a tunnel. Trying to clear a blockage by hand, he was buried and suffocated. The NCB refused to pay his widow compensation, saying he should have used the long pole he had been provided with.

1954—Mary Macadam, an old lady with a remarkable life story. She was born in 1882, in an old fortified house in Kilmadock, Stirlingshire. Her mother was an unmarried domestic servant there; her father was not listed on her birth certificate. In time, Mary became a domestic servant, too.

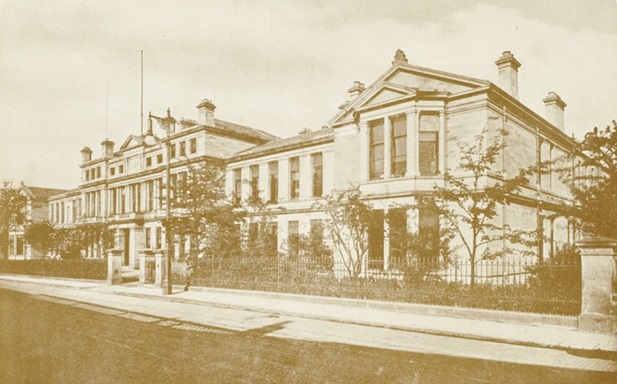

In 1909, when she was twenty-seven and working as a maid for an elderly couple in Leven Terrace, by the Meadows in Edinburgh, she became gravely ill with tuberculosis. Too weak to work, and with no family to support her, she was admitted to the Longmore Hospital for Incurables, on Salisbury Place, a relatively new institution that had been established for patients who required long-term care or were not expected ever to recover.

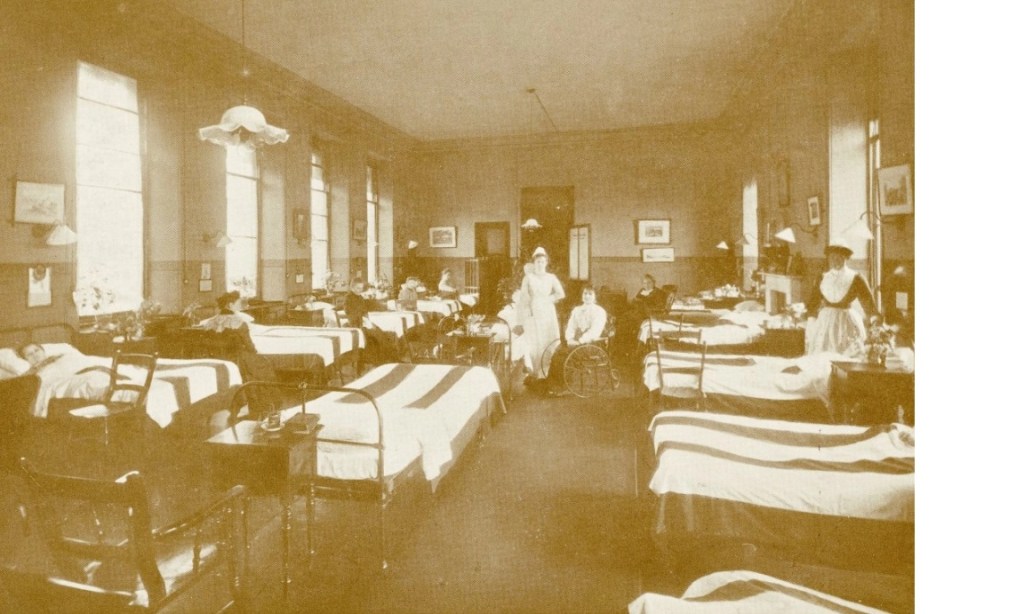

She spent the next thirty-four years there, mostly in ward 2. This photograph was taken during her time there. She may even be in it.

Later, she recalled her fellow patients, such as an old man who counted the matches in the boxes that were brought to him and was outraged if there were too few, and Mary Marr, completely paralysed by arthritis, who read the news to the ward if a paper was propped up in front of her. There was a girl who was in for seven years with spinal trouble and was often visited by a young man. Mary said: “One day he proposed, right at the foot of my bed and said he would come back for her answer next week, and that he would give us all a party if she said yes. She did! And we were all invited to the wedding. I couldn’t go, but I got a piece of cake.”

There was also a missionary woman who had contracted leprosy and passed the remainder of her life in isolation in a hut in the hospital grounds, her meals passed to her through a small hatch in the wall.

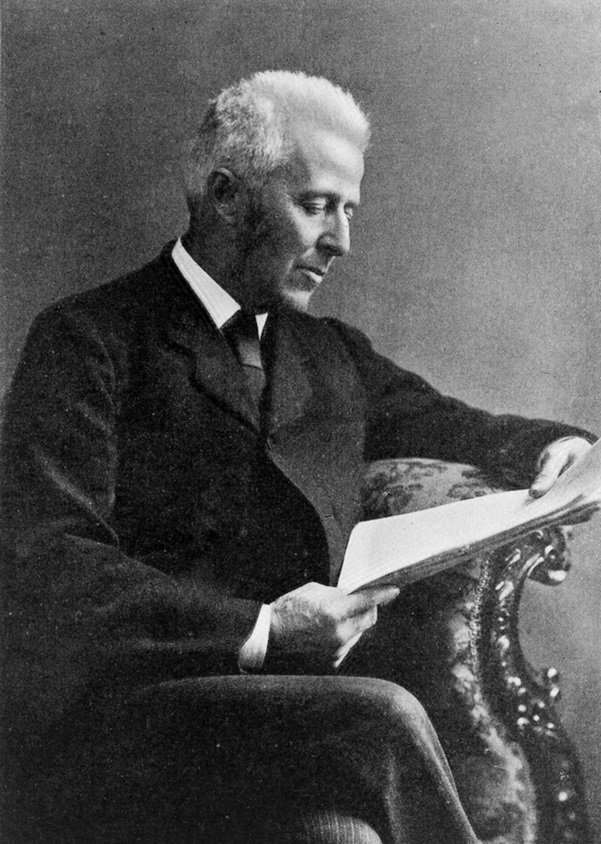

And Dr Joseph Bell, Arthur Conan Doyle’s inspiration for Sherlock Holmes, was one of Mary’s doctors—“Dr Bell always called me his ‘bright lassie’.”

In 1943, at the age of sixty-one, Mary was deemed to be cured of tuberculosis, but the disease had affected her eyes, and she was transferred to the Thomas Burns Home for the Blind, a few streets to the south.

After some time—months? Years?—her eyesight improved sufficiently for her to move into a flat in the East Crosscauseway tenement. A job was found for her in the Royal Infirmary, “looking after the salt cellars and pepper pots in the staff dining room.”

She packed her flat with ornaments, pictures and cards from friends—“I have spent so long looking at bare walls I can’t have too many things to look at now.”

Throughout the 1950s, she wrote to the Evening News with reminiscences about her years in the hospital. In one letter, she wrote, “I have never forgotten the many examples of courage and quiet endurance I witnessed in hospital and give thanks that, although not strong, I can still carry on in a quiet way.” She concluded: “I have a nice little home of my own, and a nice little post in the Royal Infirmary, and I have many good friends.”

Mary died in 1971, at the age of eighty-eight, of a stroke, in a Craigmillar Park nursing home. The hospital for incurables is now the headquarters of Historic Environment Scotland.

1939—William Wooler, 55, whose request for a divorce from his wife, who had left him in 1925, was refused because he admitted in court that “since 1934 he had committed adultery on a few occasions, the last occasion being in 1938.”

1930—John Black, arrested for loitering outside the tenement, betting slips about his person. A £10 fine did nothing to deter him; he had been caught in the same spot once before and was arrested there several more times in the 1930s, the fines increasing to £25 before he either gave up or moved on.

1906—Mrs Lauder, who was looking out of her rear window when she saw “two figures dimly silhouetted against the light” in the yard behind Alexander’s boot shop, which fronted onto St Patrick Square. She “became suspicious that the men were after no good” and went out to tell the police. By the time the police arrived, the men had squeezed themselves between the stanchions of the shop’s back window, stolen two pairs of boots and squeezed back out. “It seemed the birds had flown, but diligent search resulted in their finding one man, James Ross, crouching in an adjacent yard.” The other burglar, Thomas McIntyre—whose description Mrs Lauder had given to the police—was arrested when “curiosity as to the fate of Ross evidently overcame his discretion” and he was seen loitering in the vicinity of the police office.

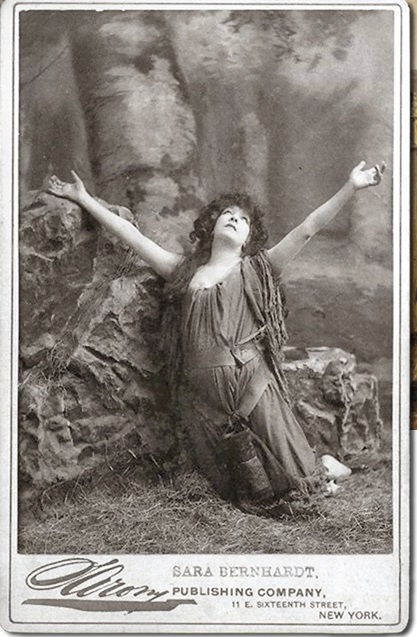

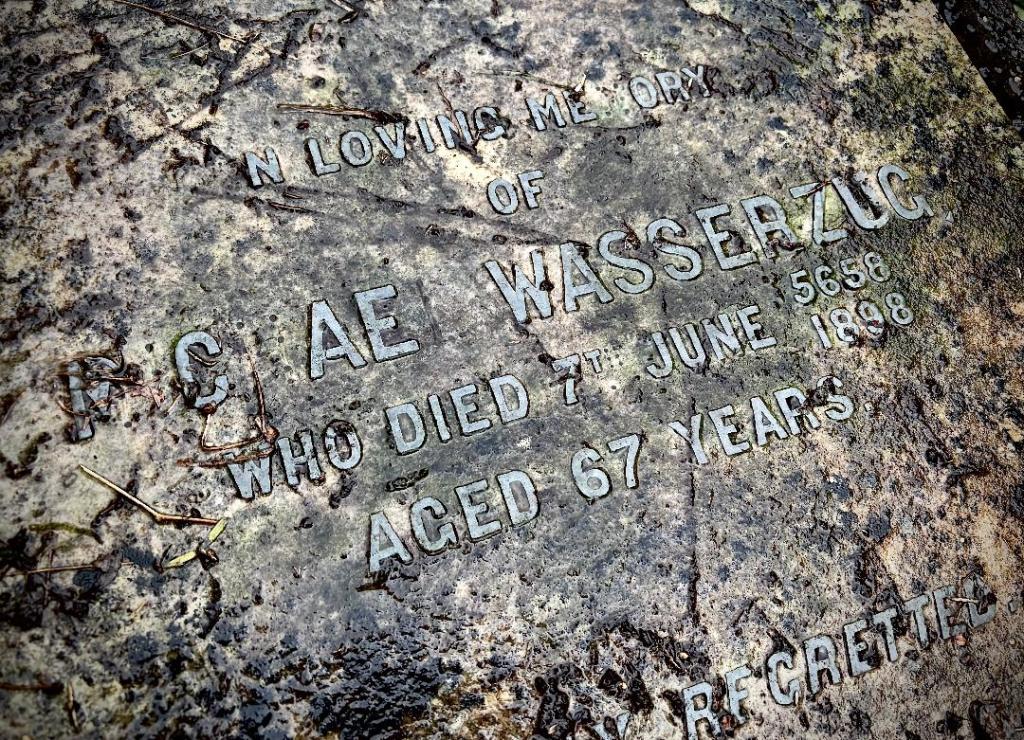

1889—Michael Wasserzug, jeweller in the High Street. A daughter, Rachel, died of scarlet fever a month before her third birthday; a son, Henry, died of tuberculosis aged 26. Great misfortunes, unremarked by the press. A lesser one made the papers: In 1881, “so great was the crush of people at the Theatre Royal last night anxious to see Mdme. Sara Bernhardt” that Michael “was severely injured on entering the gallery. He had to be carried out, and was conveyed home. We believe some of his ribs were broken, and his back was considerably injured.”

Michael died in 1898, aged 67, his sclerotic arteries unable to convey blood to his extremities, which blackened and withered away, and was buried in the Jewish section of Newington cemetery.

1879—Isabella Milligan, 25, who, after six years of marriage to Adam Hay, a baker, withdrew her personal money from the bank, gave Adam £10, and left for Glasgow with their lodger—Thomas Thomson, her husband’s foreman—never to return.

In 1854, the old drain beneath the tenement was so decayed and clogged that “the universal experience of the locality” was “that at night the smell is so strong and so offensive in the houses, ‘that it is just like lying beside a decomposing corpse.’” After complaints, the Paving Board visited and found “the putrescent contents [of the drain] were belling up through the road metal, and sending forth a stench enough to make a strong man sick” and that “there can be no doubt that the ground flats are saturated with the contents of this drain.”

The drain was, we can only hope, fixed and the sewage-soaked masonry dried out by the late 1880s, when the shop at no.23 (the boarded-up windows to the left of the stair door, above) brought a new aroma to the street: “Now opened, The Fish Shop … fresh supply every day.”

In the 1920s, the premises became a confectioners, run by Joseph Rovira (frequently fined for selling cigarettes outwith the licensed hours). After he died of bronchitis at fifty-five, his wife ran the shop, until her daughter, who worked with her, died of tuberculosis in 1937.

That ended the premises’ life as a shop. It became the backroom of Findlay’s chemists, which had a shopfront around the corner, and was used for the manufacturing of Violiv hand cream, advertised as a “marvellous treatment for roughened hands”.

The west side of the tenement is on St Patrick Street, which makes up part of the stretch between Nicolson Street and Clerk Street.

During the second world war, 6a St Patrick Street (ground floor left) was a Food Advice Centre, run by the Ministry of Food, which gave people information about subjects such as how to prepare salad and vegetable dishes, in which the Scottish diet was perceived to be lacking. Its publicity said: “The Scots 150 years ago ate more vegetables than the English, but today Scotland lags behind in this respect, and in this lag lies danger to our national health. A tendency to headaches, bad gum conditions and over-tiredness may be traced to a lack of green vegetables.”

From the 1820s to the 1870s, 6 St Patrick Street (the premises on the right, above) was the emporium of William Ronaldson, who sold drinks such as Patent Rye Gin and Imperial Porter: “This Rich and Delicious BEVERAGE, which is highly recommended by the Faculty for its strengthening and stomachic qualities, to be had at 6s per Dozen, in creaming condition”.

For most of the 20th century, prior to becoming Boots in 1993, it was Findlay’s chemists, of which a corroded sign is all that remains.

Addendum:

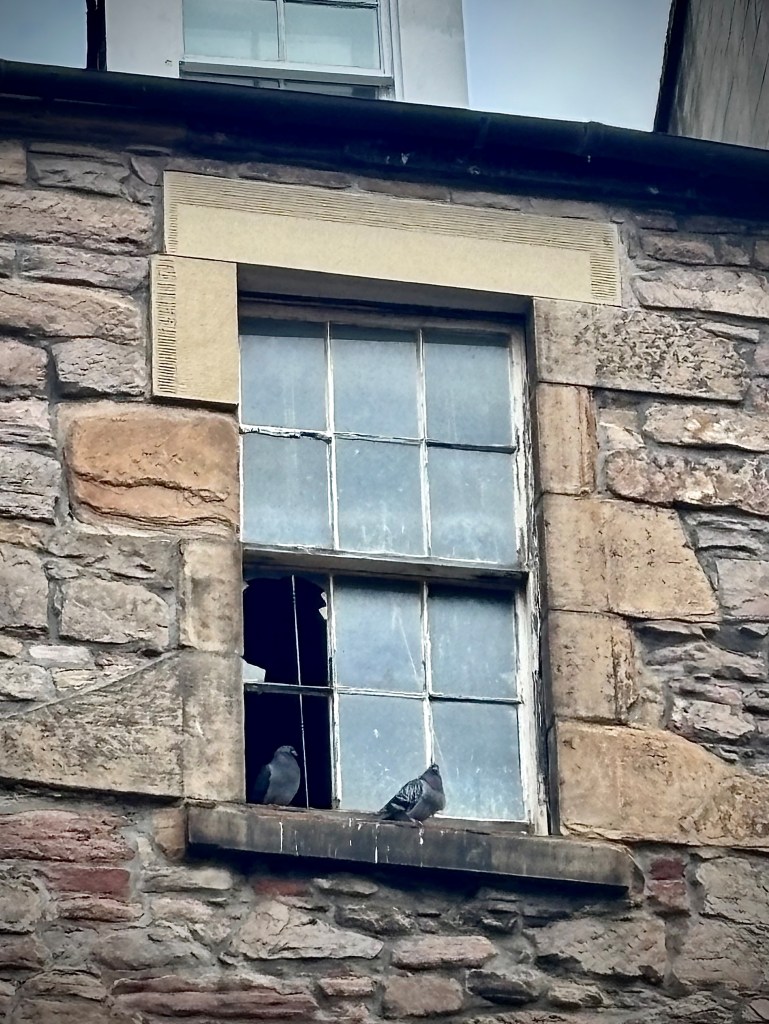

The third-floor flat has been empty for some time, but this winter, thanks to ancient putty finally giving way, the vacancy ended, and the tenement welcomed its latest, non-rent-paying, residents.

Thanks Diarmid – Want to do your version of this? Donated, I’m afraid. Mike

https://buildedinburgh.substack.com/p/my-favourite-building-stephen-jardine My favourite building: Stephen Jardine and Prestonfield House buildedinburgh.substack.com

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating stories as ever but how uplifting to read of Mary Macadam, surviving to 88 after everything she’d been through.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Was Mary Macadam born at Old Newton of Doune, Diarmid?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! Indeed she was. Nice deduction! At the time Mary was born, the place was owned by Miss Mary Campbell, a daughter of Robert Campbell, writer, Stirling. She took up residence in 1862 and died there in 1891 at the age of 80.

LikeLike

Interesting, thanks. Four years previously in 1858 John Campbell, a Glasgow merchant, bought the house from the Edmonstones. It’s still owned by Campbells now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Her brother was “the late John Campbell of Inverardoch, Doune” — presumably the same guy. (the “late” bit comes from the notice of her death in 1891). Fascinating that it’s still in the same family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, yes, that makes sense. John had Inverardoch built to the south of Old Newton to a design by David Bryce. He died in 1882 and the “new” house was demolished in 1950, but there are still remnants of the estate there.

LikeLike

Excellent info as always. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed it thoroughly, as always. Thanks. NB: A higher-resolution version of the picture of Joy Wilson can be found at https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/heritage-and-retro/retro/the-age-old-edinburgh-tradition-of-washing-your-face-in-the-may-dew-2651961 (I was looking for more information about the May Day dawn pilgrimage and stumbled upon it).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Remco! I’ve updated the picture — much better now!

LikeLike

What a great read. Thank you as always for the expert research and excellent writing. I especially enjoyed the payoff at the end. Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you – really enjoyed this.

My daughter spent her junior year abroad (2005-2006) at Edinburgh University and lived just off Newington. When she went back to graduate school, (2008) she lived at Salisbury Mews. There, she met her future husband and their first flat was on Causewayside, next door to the Tesco Express, across the street from the Map Library (not its official name, but you probably know what I mean), and around the corner from Historic Scotland home office. I became very familiar with that part of Edinburgh. I live in Berlin and visit them often – from student days in Salisbury Mews, to Causewayside, to East Fountainbridge, to where they are now on St. John’s Road in Corstorphine, just down the hill from the nature reserve and walled garden.

I love Edinburgh and love learning about lives of regular people who have lived there.

Thank you for your work!!

Best regards,

Carol Himmelman-Christopher Berlin, Germany.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks again Diarmid. Always a fascinating read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very enjoyable and well written and researched. All my family is from Edinburgh, and my father’s family were all Southsiders, so I am especially interested in the stories from that area.

LikeLike