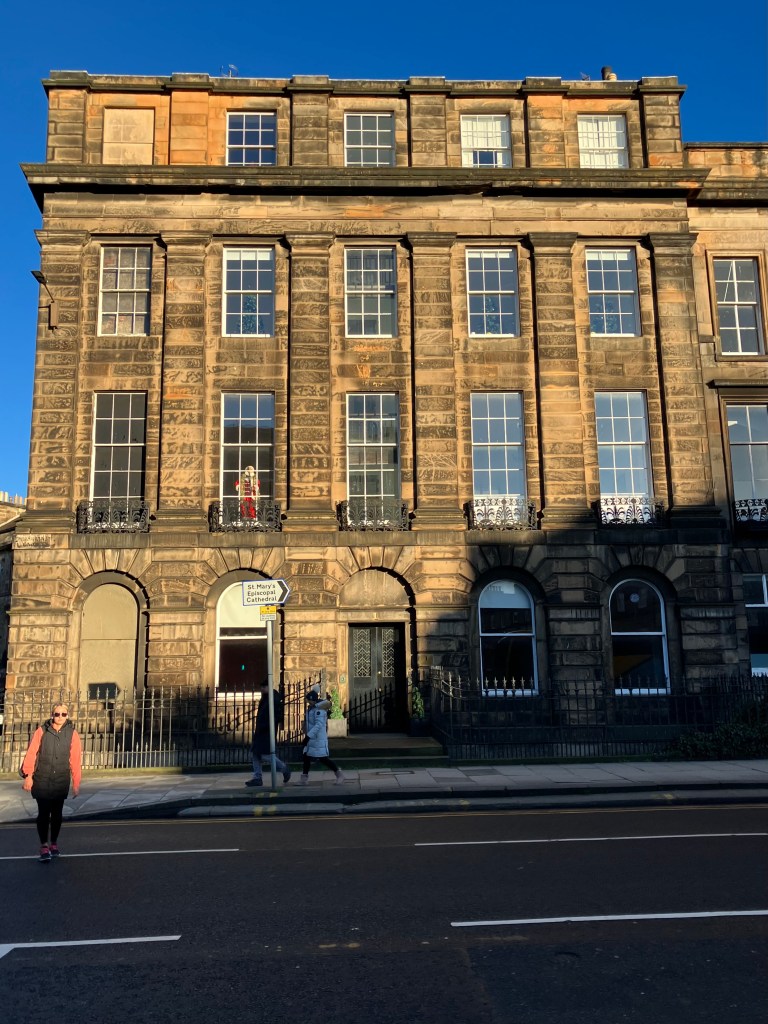

1 Randolph Place—an upper-class Georgian tenement on a street named after a nephew of King Robert the Bruce, on the edge of the exclusive Moray estate. Built as three floors of flats over a two-storey ground-floor/basement flat.

Former residents include:

1940—Captain John Fiskin Halkett, retired shipmaster and the last of the Halketts who had owned a flat in the tenement since the mid-19th century, when his grandfather made his fortune raising crops in Entre Rios, Argentina. (A street in Gualeguay is named after the family.)

At the time of his death, John’s Edinburgh address was Over-Seas House, a club on Princes Street. He had sold the Randolph Place flat in 1929, after the deaths of his unmarried aunts (in their 80s and 90s), who were the last Halketts to live in the property.

1903—William Agnew Ralston, the head of Tod, Thomson & Co, a Leith firm that produced oil cake for farm animals and sold manure to farmers. He left Randolph Place when he inherited Binny House, a mansion in West Lothian.

The Binny estate had been granted to William Binnock by King Robert the Bruce in 1313, and the quarry on the grounds had supplied the building stone for many of the grandest Victorian buildings in Edinburgh, including the Scott monument and the galleries on the Mound.

After William died—at the age of 63, of kidney failure and blood poisoning—Binny House was home to a succession of wealthy Edinburgh accountants, before becoming a cancer hospice and then, finally, a hospital specialising in teenage eating disorders, which closed in 2001.

1895—Robert Wilson, captain of the ship Clan Graham, who died along with some of his crew during an outbreak of Yellow Fever in Rio de Janeiro .

1889—G P Glendinning, the chief manager of the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation during the 1885 Burmese war, which was a British invasion and annexation of the country, the pretext for which had been some slight interference with his company’s teak exporting business.

1858—Anna Crichton, who had come to Edinburgh for the birth of her second child. Her husband, William, an engineer, had remained in St Petersburg, where the happy fact that his great uncle was the Tsar’s personal physician had saved him from imprisonment during the Crimean war.

William, 1st Lord Crichton, one of the de facto rulers of medieval Scotland during the years when James II was a child king.)

They later moved to Turku in Finland, where William established a company building warships for the Imperial Russian Navy, and Anna became mother to fourteen children. (A street in Turku is named after the family.) She died in 1924, at the age of 91.

1854—Rev Richard Hibbs, a controversial English outdoor preacher who was brought to Edinburgh to be assistant minister to an Episcopalian clergyman who wanted to found a “Church of England in Scotland”.

Two years later, however, Richard alienated his colleagues and the small congregation by denouncing all who had attended performances of “Don Giovanni” and publishing a censorious pamphlet entitled “Remarks Upon the Introduction of the Italian Opera into Edinburgh”, which called the opera “a polluting production … and … a poisoned feast” and the theatre itself “the synagogue of Satan”, where people would fall into “a course of immorality and sinful, sensual gaiety”.

Richard was dismissed, and returned to England, where he resumed outdoor preaching, gathering crowds of hundreds of people with his energetic and polemical sermons, and was often arrested for causing an obstruction. He died in 1886, aged 74.

1845—Elizabeth Barron, whose daughter Marion died in the family home at the age of three. Present at the funeral of Elizabeth’s daughter were her father, Alexander Adie, a maker of scientific instruments, whose most successful design was the sympiesometer, a barometer for ships, which contained hydrogen and almond oil instead of mercury; her brother John, who was a partner in their father’s firm and would shoot himself twelve years later after suffering “fits of despondency”; and her brother-in-law Thomas Henderson, who, in the late 1830s, had become the first person to calculate the distance from Earth to Alpha Centauri, although, lacking confidence in his work, had delayed publishing his findings for so long that a German astronomer got the credit.

Elizabeth’s husband, George, a lawyer, died in 1851, at the age of fifty. In her later years, Elizabeth lived with her daughter Janet and her husband Franz Hedrich at 6 Roseberry Crescent.

Franz was a poet who had been a member of the Young Bohemian literary circle in Prague. He met Janet in Europe, where the pair lived “a varied course of life” and lost a lot of money gambling in Monte Carlo, before settling down with the aged Elizabeth in Edinburgh in the 1870s.

When Elizabeth died in 1892, she apparently left everything, including the house, to Janet and Franz. Naturally, the four other surviving children contested the will.

The court case dredged up family grudges, and made public old claims that Franz had been blackmailing the Austrian author Alfred Meissner for years—with threats to announce that he had written several of Meissner’s major works—and that the resultant stress had driven Meissner to suicide.

A news report said, “Bit by bit the process of tormenting and destroying the weaker nature of the unhappy, tortured Meissner went on, and the grim tragedy of friendship ended in the outraged distraught spirit of the poor sufferer seeking in the repose of death the rest and peace denied him in life.”

Franz conceded that he had befriended Meissner as a young man in Prague and had, in fact, in recent years agreed to have his own works published under his friend’s more marketable name.

He revealed that he had placed cryptograms in some of the books in case he ever needed to prove the writings were his. For instance, he had arranged the initial letters of the opening sentences in chapter 50 of “Norbert Norson” to yield the word “Hedrich”.

Also, he claimed that, in the same book, he’d given the Italian-sounding but entirely invented name of Chiuderato to a character because it is an anagram of “Hedrich Autor”. (It’s actually an anagram of “Hedric Auto”, but—close enough?)

However, he denied the charge of blackmail, saying that, through vanity, he had merely asked Meissner to acknowledge his authorship of the novels, and that Meissner had killed himself due simply to “an acute disorder of the brain”.

Eventually, the siblings who had once played together in their flat in Randolph Place settled out of court, on condition that the imputations against Franz be withdrawn.

Franz died a few years later and is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard. “Norbert Norson” is out of print, but a recent edition of Meissner’s “Die Prinzessin von Portugal” credits him as co-author.

1844— Patrick Oliphant, retired captain of the Madras Native Infantry, who had a country seat in Fife—where he was “famous locally for his fervent Christianity and prize-winning cattle—and used 1 Randolph Place as a town residence.

At the age of 48, he married the 18-year-old Mary Colville, whose father told him about the solemn disinterment, after 500 years, of the bones of King Robert the Bruce, which he had witnessed in Dunfermline abbey in 1819.

As the king’s skull was held up to the assembled dignitaries, “it was pleasing to observe a solemn stillness reign, betokening the feelings of reverential awe, awakened by the recollection of the noble spirit that once animated it, contrasted with the present humiliation of its mortal tenement.”

1843—John Steell, the preeminent sculptor of his time, who carved—using stone from the Binny House quarry—the statue of Queen Victoria that overlooks Princes Street from the roof of the Royal Scottish Academy, and the statue of Sir Walter Scott that sits in the Scott monument.

The 25-ton marble block for the Scott statue arrived in Leith from Italy in 1844, after nearly sinking the first ship it was loaded on to. More than a hundred dockers arrived at work early “in order to be the first, as they said, to set in motion the block that was to form the statue of the illustrious author”. They pulled the truck, on rails made of boiler plates, from the wharf to Junction street, where “twenty of the most powerful horses in Leith” were harnessed to it.

Followed by an ever-increasing crowd of spectators, they pulled it slowly and with great effort up Leith Walk, the wheels leaving indentations in the surface of the road. At the even steeper incline of Leith Street, “the horses were put to their speed in a gallant style, amidst the cheers of the spectators, and the hill was gained in a short time.” They progressed along Princes Street, the crowd giving out more cheers as they passed the unfinished monument, until they reached John Steell’s studio at the end of Randolph Place, where the statue was finished in a matter of months.

Twenty-three young stonemasons died within four years of the completion of the Scott monument, their lungs destroyed by the silica dust that filled the air in their workshops. John Steell, working primarily in marble, lived to the age of eighty-six.

The tenement’s ground floor flat is entered from around the corner (1 Randolph Crescent), and has been the home of lawyers, doctors and surgeons for most of its life. Around 1914, it became a training centre for domestic servants.

During the first world war, Miss Constance de la Cour, one of the trustees of the training centre, converted it into the Soldiers and Sailors Help Society (“to assist those permanently disabled during the war”). In 1917, after it transpired that there were going to be more permanently disabled men than ad hoc charities could cope with, she converted it again to the Navy League Comforts Fund, where people could donate “books, 7d novels, magazines, card and musical instruments for the distraction and amusement of the officers and men of His Majesty’s Navy.”

In the late 1930s, it was the home and surgery of R Cranston Low, a dermatologist who wrote “Common Diseases of the Skin”, “The Atlas of Bacteriology” and an essay entitled “Queer Patients” recalling some of the strange cases he had treated in his practice.

The final case in the essay concerns “a lady about 60 years of age” who came to him with a matchbox that she said contained caterpillars that had come wriggling out of her skin in their hundreds. He wrote: “She gave a long rambling story to the effect that her son had returned from South America some months ago, and had been staying in her house. He was suffering from ‘a loathsome itchy skin disease.’ She maintained that as the son slept in the bedroom above hers and scratched his skin at night, the beasts fell off his bed on to the floor of his room, came through the ceiling of her bedroom and fell on to her as she lay in her bed below.”

Cranston opened the matchbox, and examined the caterpillars, which turned out to be simply pieces of epidermis that the woman had rubbed off her skin. She told him he was wrong, and that there were animals in her skin which were invisible until she rubbed it.

He wrote: “She opened her bag and produced a small pot of white ointment. Then she pulled up the sleeve or her left arm and putting a little of the ointment on the fingers of her right hand, proceeded to rub the left forearm up and down steadily. After she had rubbed a short time the ordinary pieces of rolled-up surface epidermis, which one can produce by rubbing the skin when it is soft in a hot bath, began to appear. As they were elongated and black-looking, they looked not unlike small caterpillars. Whenever these caterpillar-like pieces of skin began to appear, she became quite excited and rubbed harder than ever. She seemed terrified by them, but it was with difficulty that she was persuaded to stop rubbing and calm down.”

The problem was clearly a mental one. Cranston made an attempt to remove the delusion by suggestion, giving her calamine lotion and telling her that if she put it on night and morning for ten days and did not scratch or rub her skin, the condition would disappear.

“This, however, failed completely,” he admitted. “I lost sight of the patient, and do not know what happened to her eventually.”

Today, the flat is the office of a structural engineering firm called Acies, which takes its name from the Late Latin word for steel, a (no doubt unintentional) link with the sculptor who once lived upstairs.

Low’s “Queer Patients” reminds me of “Devil’s Bait” in Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams. Her travels to understand groups of people with Morgellons disease are fascinating. Your research on Randolph Place is wonderful. I appreciate your work. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks for writing. I hadn’t heard of Morgellon’s disease but, having just looked it up, it sounds exactly like what the poor woman was suffering from. Very interesting — thanks so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I spent some time looking into the residents of the nearby Randolph Cliff few years back when I was asked about the mysterious Sailor statue which overlooks the water from the gardens of the Moray Estate . Unfortunately not much exists about the statue but I often thought it must be related to John Steell – the sculptor connection so nearby is certainly interesting. Thanks for this!

LikeLike

If I ever come across anything on it, I’ll let you know.

LikeLike

So entertaining!

LikeLike

Those poor young stonemasons. Very much enjoying Tenement Town. Please keep adding to the catalogue.

LikeLiked by 1 person