20 Rankeillor Street, Edinburgh—built around 1820. Eight flats in the stair, over two ground-floor flats. Notable former residents include:

1960—Harry and Elma Murdie, whose children, born in the ground-floor-left flat, were the fourth generation of Elma’s family to live there, going back to James and Elizabeth Marsden, “makers of corsets and ladies bandages”, who moved in around 1915.

1953—Euphemia Glasgow, 81, knocked down by a lorry as she stepped off the pavement in Clerk Street.

1923—Janet Bain and Christina Archibald, who were fined £1 for the theft of 51 cakes, 24 buns, 15 eggs and three-quarters of a pound of butter from the baker’s shop where Janet worked.

1918—James Marsden, only son of James and Elizabeth (above), whose corset-making business propelled James through the Royal High School and Edinburgh University, where he gained a BSc (Distinction) four years before being killed in action in northern France.

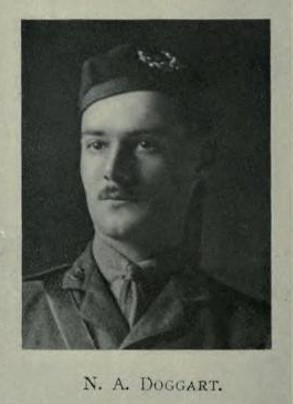

1913—Norman Doggart, a Kirkcaldy boy who lodged in the ground-floor-left flat while studying arts and medicine. He joined the air force and died in Oxfordshire in 1918, when his Bristol F2 biplane “stalled on a gliding turn” and crashed. He was 27.

1889—Rev Lockhart Dobbie, who came to Edinburgh after failing health forced his resignation as minister of a rural church in Lanarkshire. After settling in Rankeillor Street, his wife, Nellie, gave birth to a son who became the latest in a line of Lockhart Dobbies going back to 1805, in Airdrie.

Lockhart earned a living as a minister without a church, conducting services and performing weddings and funerals around the city as required. Nellie grew ill, undone by neurasthenia—a Victorian term for the long weariness of the soul: depression, anxiety, sleeplessness, lassitude.

In 1909, she died of heart failure, aged 47. Lockhart, then aged 69 and still in poor health, hanged himself three months later.

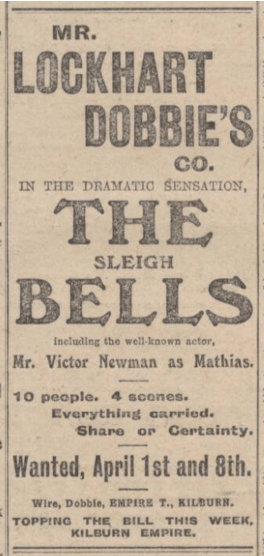

When his parents died, the 20-year-old Lockhart Dobbie was just embarking on an amateur dramatic career, acting in short pieces written and produced by his elocution teacher. In 1912, he established his own company of players and took it on a tour of the provinces.

There appear to have been no reviews of the production, and no further tours. Lockhart died in hospital in 1960, of a stroke.

1896—Dr George Munro Stocks (ground-floor-left), who was called to attend a young woman in a tenement in Nicolson Street who was unknown to him—Alice Davidson, eighteen years old, a lithographic printer, who was “in great pain and very ill.”

She told Dr Stocks that she had taken “a particular kind of decoction given to her by a woman” and showed him a packet containing crushed dried leaves—evidently some sort of abortifacient—and said that she had been visited by two young medical students who had performed “some kind of operation” a few days previously. It was they who had left the urgent message asking Dr Stocks to visit.

He gave her morphia and told her to rest. However, she was no better the next day, and worse the day after that, so he gave her liquid extract of ergot, which he hoped would stimulate uterine contractions and expel any foetal tissue the medical students may have left inside her. It had no effect.

After five days, “he found her so collapsed that he considered it his duty to save her life by instruments.” As he thought her too weak to withstand chloroform, he performed the manual evacuation of the uterus without benefit of anaesthetic.

She died ten days later.

A post-mortem confirmed that Alice had undergone an abortion; Dr Stocks was charged with murder, brought before the court, then “handcuffed between two pickpockets and conveyed in custody to the town gaol”, where he remained for two weeks, awaiting trial, until uproar from the medical community—the BMJ called the case “a startling misuse of the powers vested in the representatives of the Crown”—won his release; all charges dropped.

The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch, outraged on the doctor’s behalf, noted that “Dr Stocks was released by means of a note whose laconic and curt tone of officialism touches the sublime, the like of which might be written to announce the release of a dog”, and the BMJ declared that the responsible functionaries, from the “blundering policeman” to the “careless police solicitor”, should be censured in Parliament. That did not transpire.

Dr Stocks married his fiancée later that year, and continued in practice into the 20th century.

1887—Jacob Glasstone, who died of whooping cough, aged eight months.

1884—Agnes Glasstone, who died when she fell and fractured her skull, aged nine.

1883—Baby Glasstone, name not recorded, stillborn.

1874—Samuel Glasstone, father of the above children, a Russian Jew who arrived in Scotland with his parents around 1860. His father went into business as a picture framer, and Samuel followed him into the trade. When he was 25, he married Isadora Mayer, the daughter of another picture framer.

(They had eight other children— Paulina, Isaac, Louise, Henry, Solomon, Reuben, Jacob and Floretta—who all survived into adulthood.)

Samuel died of a heart attack in 1909, aged 60, in Newcastle, where he had opened his own picture framer’s (“Deathblow to Big Profits—Best & Cheapest Picture-Framing Shop in the City”). Isadora went to live with one of their children in South Africa, where she died in 1946, aged 84.

1883—Mr A C___n (ground-floor-left), who wrote to the Institute for Psychical Research to report an uncanny incident that took place on 7 January 1871, when he was living in the West Indies:

“I got up with a strong feeling that there was something happening at my old home in Scotland. At 7 am I mentioned to my sister-in-law my strange dread, and said even at that hour what I dreaded was taking place. By the next mail, I got word that at 11 am on the 7th January my sister died. The island I lived in was St Kitts, and the death took place in Edinburgh. Please note the hours and allow for the difference in time and you will notice a remarkable coincidence. I never at any other time had a feeling in any way resembling that. At the time, I was in perfect health, and in every way in comfortable circumstances. I may add I never knew of my sister’s illness.”

1883—Thomas Winton, dentist (ground-floor-left), “who has had long experiences in the first houses of London and Paris” and “manufactures and inserts Beautiful Enamelled Teeth at prices so moderate as to defy all competition.” Thomas had practised in various fancy addresses in the New Town before, in his 50th year, moving to Rankeillor Street in the southside, where, within a month, he contracted pneumonia and died of a heart attack.

1866—John Bent, from Sussex, whose studies in the medical school were financed by an inheritance from his grandfather, who had made a fortune selling sugar grown by his slaves in his plantation in Demerara.

1866—Miss Margaret Laing, who died of “Natural Decay”, aged 70—the daughter of Major Thomas Laing, who fought in the Peninsular war, where he was nicknamed “Robinson Crusoe” and shunned by the other officers due to his “not being very exact in his dress and being eccentric in his habits”.

1860—Dr James Lawrie (ground-floor-right), who owned the Sciennes Hill Hydropathic Baths, featuring a “NEW and IMPROVED ELECTRO-CHEMICAL BATH for the removal of Mercury and other deleterious substances from the body, as well as a remedy for Paralysis, Sciatica, Rheumatic, and Nervous Complaints.”

1835—Alex Peat, bookseller, who was drowned, along with his brother, when the ice cracked under a group of skaters on Duddingston loch—“these two, melancholy to relate, sank before any efficient aid could be afforded.”

Rankeillor Street was envisioned as a terrace of elegant townhouses in the style of the New Town, but only two (shaded on the map below) had been built by 1817, when a slump in the market halted construction.

Plans changed in favour of the more profitable tenement housing that would come to define the city’s new districts in the 19th century, leaving the older buildings oddly stranded in a row of taller neighbours, and giving the last Georgian residents of the southside a taste of the new age to come.

Great stuff. Please continue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this wonderful edition. I really appreciate and enjoy each newsletter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

More amazing tales. So many sad stories. And the gall of Janet and Christina; did they not think anyone would miss that amount of baked goods. Those townhouses are my dream home!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another fantastic set of stories, Diarmid! I gasped with horror over eighteen year old Alice and the doctor. The world, however savage, is, in general, a slightly better place. Cheers June Prof June Andrews OBE FRCN FCGI MA LLB RMN RGN Clarity. Confidence. Care. Every Step. http://www.juneandrews.net

Dementia the One Stop Guide

Helping people maintain brain health And navigate dementia and elder care

>

LikeLike