Corner tenement over one ground-floor shop. Built in 1896, with four floors of “superior houses of 3 and 4 apartments”. Former residents include:

1940—George Millar, engineer, who found a little boy crying all alone by the Edinburgh dock in Leith one blustery afternoon. The boy was Peter Law, and he was four years old. He told George that his big brother was in the water, and his father was in there, too.

The boy’s father—Robert Law, a housepainter—had taken his two sons to the dock to see a flock of wild ducks. The sea was rough, and a wave had swept his son Thomas into the water. Robert had dived in to help him and been lost to sight.

George, seeing something floating in the turbulence some way off, threw a lifebelt, “but to no avail.” The father and son were drowned; their bodies recovered the next day.

1938—Jane Wright, who was taken to hospital with concussion after falling off a tramcar at Bonnington Toll.

1954—Margaret Mason, a Gaelic singer, who married Angus Ruthven. Both were “popular members of various Clan and Highland Societies” and sang in the Edinburgh Gaelic Choir.

1952—June Clapperton, a twenty-four-year-old woman who received minor head injuries when she was knocked down in Princes Street by a canvas shopfront canopy that had been torn from its frame by a gust of wind.

1947—James Hamlett, a boilermaker, originally from Manchester, who had a “very tame” blue and grey budgie named Dinkie, which flew out of his front room window one summer’s day and was lost.

1945—Mary McConville, first child of Lt Cpl Thomas McConville of the military police. She was three years old, nearly four, when she died of abdominal tuberculosis.

1942—John Garside, who opened a barbershop on Crighton Place in Leith Walk in 1912 and ran it for the next thirty years. The premises later became a tailors, then a fancy goods store, and lately a blind shop. It has recently become a barbers again.

John had a heart attack five minutes into his walk home from work on a Tuesday evening in the summer of 1942, dying on the pavement outside 28 Pilrig Street. He was fifty-three.

John’s son, Edwin, who had worked in his father’s hairdressers since he was a boy, had only recently left Edinburgh, joining the RAF at the outbreak of World War 2. When his father died, Edwin was in Canada, training on Sunderland flying boats.

Later in the war, Edwin piloted a flying boat that evacuated one hundred and twenty sick and wounded soldiers from the shore of a lake in Japanese-occupied Burma, “crossing high mountains in thick cloud, flying without an escort because of the monsoon.” The photograph below shows Edwin’s plane, loaded with casualties, landing on a lake in India at the end of his mission that day. The plane was sunk by a whirlwind later that month. (Edwin wasn’t on board.)

1943—Thomas Millar, engineer, who defrauded the Ministry of Works of £100—around a third of his yearly wages—through a false claim for lodging expenses while working in Fife. He avoided jail by agreeing to pay it all back within a year.

He was the cousin of JPM Millar (below), who shared the flat with Thomas and his wife for many years. Thomas lived in the tenement until the 1970s, when, aged seventy-two, he died from sepsis caused by an infection in his bowels.

1916—Thomas Paterson, a North British Railway foreman, who had an affair with a woman named Jessie Geddes while her husband, William, a stonemason, was working in South Africa.

Jessie had refused to accompany William to South Africa in 1905, shortly after she had given birth to their first child, a daughter. William sent home 30s a week, and paid the rent on the flat. In 1912, he came home on holiday for six months, and resumed relations with his wife. A few months after his return to South Africa, he received a letter from Jessie informing him that she had given birth to “a giant baby”.

When war broke out in 1914, William had to return to Edinburgh. Jessie met him at the station and told him that their son was thriving, and that she had taken a lodger—Thomas Paterson—who was recovering from an accident and would be married soon.

When William saw his new son sitting at the fire in baby clothes and nappy, he remarked that he was big for twenty months. “Yes,” said Jessie. “He was an enormous baby.”

William may have thought it unusual that his new son, Thomas Paterson Geddes, seemed to be partially named after the lodger, but he doesn’t appear to have said so. Perhaps he had come across similarly unlikely coincidences in his time.

Before long, a neighbour told William that the boy was nearly five years old, and had been born in 1909, four years after William had left for South Africa, and three years before he had next seen his wife.

William obtained a birth certificate that proved the story, and confronted Jessie and Thomas—“You’re a fine pair, deceiving me all this time!” Jessie tried to slash her own throat with a razor but William managed to take it from her. He left the house and sued for divorce.

The judge granted custody of their 11-year-old daughter to William. Hearing the news, the girl burst into tears and said she didn’t want to go with her father, whom she barely knew. She had no choice, of course.

Jessie moved away from Edinburgh, and died in Clydebank in 1957, of a heart attack, aged eighty-four. A few years later, her son, who had moved west with her, died of lung cancer. He was fifty-one.

1914—JPM Millar, a socialist activist who founded the Edinburgh branch of the No-Conscription Fellowship and was jailed in 1916, at the age of twenty-three, for refusing to serve in the army. Traumatised by solitary confinement, he suffered “prison nightmares” for years after.

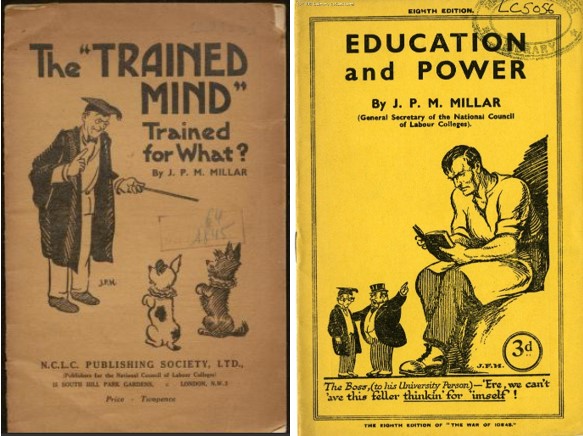

In the 1920s, he became general secretary of the National Council of Labour Colleges, then an avowedly revolutionary organisation dedicated to the complete reorganisation of society against capitalist interests, known as “the educational arm of the TUC”. In one of his many pamphlets, he wrote: “There are thousands of workers who, given a little encouragement, will transfer their interest from horse racing to the class struggle. But a working class that will not educate itself can never achieve its emancipation.”

Latterly, due in part to his vehement opposition to Communism, he moved the NCLC away from classes based on explicitly Marxist theories and—in the face of great opposition from former comrades—transformed it into a more conventional workers education service.

He died in 1989, aged ninety-six. From his obituary: “He was an internationally respected figure in the field of independent working-class education. It is claimed that two-thirds of the Labour MPs elected in 1945 were former NCLC students.”

1897—Margaret Fairfoul, whose untreated syphilis resulted in a brain disease that caused bizarre, uninhibited behaviour, grandiose delusions (of immortality, possession of immense wealth, incredible power and so on), seizures, muscular deterioration—and, at the age of fifty-six, her death.

The discovery of penicillin led to the virtual eradication of paralytic dementia but came three decades too late for Margaret.

The tenement’s corner flat was once a shop where, throughout the 1970s, Bobbette Fairlie, “a clever young designer”, sold Scottish novelties such as a “Rabbie Burns Beastie”, “Hamish the Haggis” and white heather encased in plastic, suspended on a tartan ribbon. She said, “If you are in the souvenir business and consider yourself above using tartan, you may as well forget it. You can’t please yourself. The things you like don’t necessarily sell.”

Her best seller was a line of plastic pipers inside miniature bottles bearing the slogan “Frae Scotland”, which can still be found from time to time in auctions of whisky ephemera, where they fetch around £8.

Always happy when a Tenement Town hits my inbox. Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you for a truly fascinating read, on a Monday morning. I have always wondered about who lived in/what went on in these older tenements. What life was like for ordinary folk!

LikeLike

JPM Millar, he’s the man for me! I’ve always been wary of the Marxist cohort, and couldnae find a place without their them. So.

LikeLiked by 1 person