13 Blackfriars St, Edinburgh—currently eight flats (after modernisation); probably more in the 1870s, when it was built as working-class housing to replace the “rotten, ruinous old buildings” and the “congeries of dark and wretched lanes” of the area.

Former residents include:

1961—William Balloch, who was cleaning the first-floor windows of 4 Torphichen Street when he lost his balance and fell 30 feet into the basement area. He survived!

1940—Frank Slaven, a soldier who “in an exuberance of national zeal” kicked in the plate glass window of Nicola Valentino’s shop in the High Street during an evening of anti-Italian riots. “I was thinking of what my pal had gone through at Dunkirk,” he explained.

He was a slater after the war, and died in 1951, when he fell from the roof of the McEwan’s brewery in Fountainbridge.

1936—Peter McKinley, a well-known Edinburgh boxer who was fined £2 for causing a “general melee in the bar of a public house” and “knocking down a man by striking him on the face with his fist” after he felt someone putting their hand in his pocket.

1925—Alexander Plenderleith, a window cleaner who fell off his ladder while cleaning the windows of a Leith Walk billiard hall. He recovered in hospital and lived a further eight years, dying of tuberculosis aged thirty-three.

1924—James Smith, who was fined £1 for terrifying his wife by drunkenly throwing his dinner around the kitchen, throwing crockery and other articles about the house and burning his clothing on the fire. “Conduct of this sort was a regular feature every Saturday”.

1924—Catherine McKinley, a twenty-three-year-old music hall artiste who met Abraham Shulman, sometime pianist in local band the Four Rascals Dance Orchestra, while they were both working in the Shulman cabinetmakers warehouse in the Cowgate.

Abraham “began to pay her attention, professing love and affection for her”. Before long, all his professing led to her becoming pregnant. Summoned to her flat to discuss matters, he found the place “filled with her relatives and friends”—including her brother, Peter, the boxer (see above)—who insisted forcefully that he should marry her. He agreed, but, he later said, “only in order to escape the house unharmed.”

The wedding was set for a month’s time but “on various excuses” Abraham broke off the engagement. Catherine sued for £250 damages in respect of breach of promise but seems to have lost, with Abraham telling the court that the promise had been extorted “by force and fear”.

Catherine was still unmarried twelve years later, when she and her mother were admitted to hospital with food poisoning. Abraham never married, and died at the age of sixty-nine in 1979.

1922—George Murphy, who, along with his friend Robert McCubbin, was jailed for a month for “an entirely unprovoked assault” on a journalist, whose glasses were broken when he was punched in the face. “We were drunk and didn’t know what we were doing,” said George.

1910—Owen Kellan, 13, who was trying to jump into the cab of a moving lorry but slipped from the grasp of the driver and “fell under one of the hind wheels, which passed over his body.”

1908—Margaret Sinclair, who moved in to a third-floor flat with her family when she was seven. At 13, she became a French polisher at the Shulman cabinetmakers in the Cowgate; at 21, she was a cabinet polisher in a biscuit factory; and, at 22, she left home to become a nun.

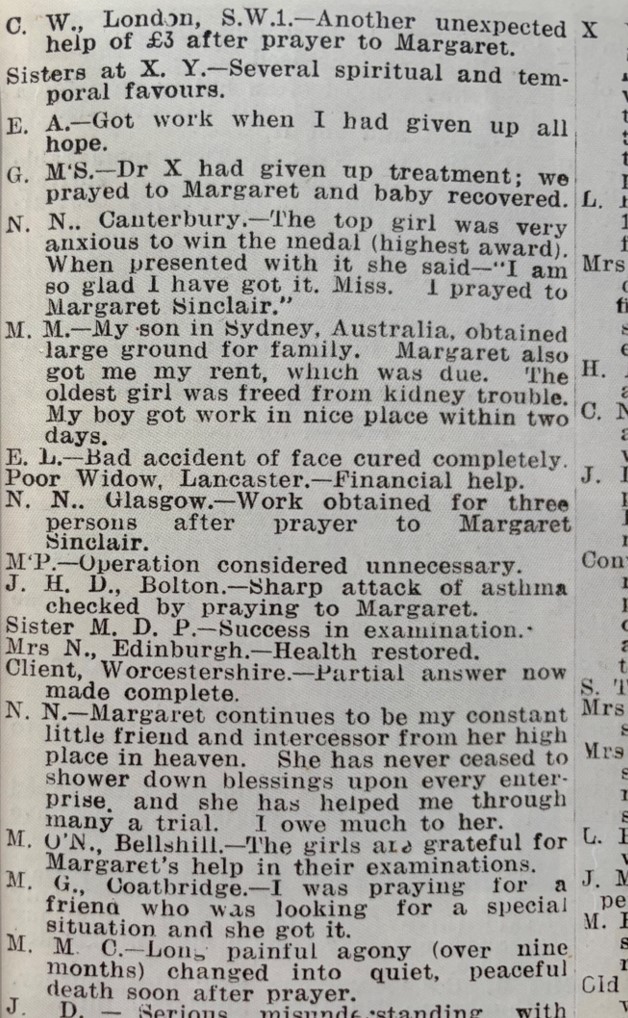

Two weeks after finishing her novitiate period in a Poor Clare convent in London, she began coughing up blood. Diagnosed with tuberculosis of the throat, she lingered in great pain in a Catholic sanatorium, and died within months. Shortly after her death, the convent received funds for long-overdue repairs, which the abbess suggested might have been due to Margaret interceding on the convent’s behalf. Soon, people began praying to her, and there were growing reports of favours gained by her intercession.

The abbess wrote, “She seems to be a great help and source of encouragement to the working classes to whom she belonged and who turn to her for help in every need”. A committee was set up to record all claims of such favours and cures (which came, in time, from across the world).

In 1942, the Vatican declared her a “Servant of God”, the first step on the road to sainthood. Until the late 1960s, her family opened up the flat to visitors every weekend, with her bedroom kept much as she’d known it in life.

Margaret took her second step to sainthood in 1978, when she was declared “Venerable”. (There are two more steps, both involving verifiable miracles.)

In 2003, her remains, having been transported in 1927 from her grave in London to Mount Vernon cemetery, were interred in a side chapel in St Patrick’s church, in the Cowgate, where she was baptised just over a hundred years before. (A room by the entrance to the church has been set aside as a museum of her life and is well worth a visit.)

1897—Dan McCormack, a blackface minstrel performer billed as “the favourite negro comedian, banjoist and dancer”.

1897—Max Benjamin, a Jewish tailor, originally from Russia, who was about to go out to the theatre when he received a message asking him to report to the central police office on the High Street. His evening was about to take a strange turn.

He arrived to find a young lady in a rich black silk dress standing at the front desk. The police told him she was Teresa Ulfeld, a Scandinavian who had little English, but could speak German and some broken Russian. Max agreed to serve as interpreter.

In the superintendent’s room, she said that she had no family whatsoever, and had travelled through Berlin, Stockholm and Moscow as a lady’s companion before leaving her service and travelling by boat to Granton and taking a room in a temperance hotel in Leith Street.

She said she had no friends in Scotland, other than a woman she had met on the boat who was visiting Glasgow before travelling to America. Also, she had hardly any money, her purse having been stolen by a pickpocket in Waverley station shortly after her arrival the previous week.

When asked why she was in mourning dress, she told Benjamin of a love affair that had ended in the death of her betrothed two weeks before the marriage. “This, and her monetary troubles seemed to affect her acutely.”

The police asked why she carried a revolver—“This query seemed to affect the lady.” Max noticed “a quiver in her eye” and that she had a letter in her hand, “which she slowly tore, first into large pieces and these in turn into atoms.”

After an hour, Max and the police went out into the lobby, leaving the woman alone, seated in a chair beside the window. They had scarcely left the room when they heard a shot. The Evening News described the scene (in prose of a quality long vanished from its pages):

“Entering the room, and filled with ominous forebodings, their worst fears were realised by finding the room filled with smoke. The visitor was in the act of falling backwards, bleeding profusely from a formidable wound in the right temple, a revolver held in her right hand.

“What had happened was too plainly obvious. The instant the lady was left alone she had produced a revolver—a neat five-chambered weapon, fully loaded—and, advancing to the mirror which adorned the mantelpiece, had shot herself in the forehead. The bullet, which seemed a large one, considering the size of the revolver, had not quite passed through the head, but being discharged through the right temple, it had travelled so far as to create a bulge of the skull on the opposite side.

“Bleeding profusely, she was removed with expedition to the Royal Infirmary. There it was discovered that the poor lady was beyond human aid, and she died a few minutes later, or about half an hour after the tragic occurrence.”

Benjamin gave his statement to the police, and another to the press, and returned home, where he no doubt followed the developments in the story in the newspapers, like everyone else.

It seemed the woman had spent three weeks in Edinburgh. “She was always dressed fashionably, her commanding form—she was nearly six feet in height—and good looks made her a noticeable figure” and “she impressed everyone she met by her ladylike demeanour and pleasing manners.” However, “of late, it was apparent that something had disturbed her, and in her last few days she lost much of her gaiety and sprightliness. She became morose and silent, and it was seen that she was giving way to grief.

“Her actions, too, left little doubt of her intention to commit suicide. Half a dozen visitors in the hotel spoke to seeing her with the revolver. In the presence of some she presented it and remarked, ‘I shall kill myself some day, and I have something here to do it with.’”

In her room, police found dozens of shredded letters—only the words “affectionate”, “adieu” and “Lord Rothesay” could be deciphered—and two photographs: one of an aristocratic young man, apparently called Alexander Romanoff; the other of a Spanish naval officer.

Romanoff was presumed to be her deceased fiancé; the officer turned out to be a Scottish engineer in the Spanish navy who had met Teresa at Waverley station after she had lost her purse, and had offered to escort her in her attempts to recover it.

A few days after her death, he told reporters, “I don’t mind saying that I fell deeply in love with her. I called every day after, and took her to the Castle, Holyrood, Roslin, Dalkeith Palace. She had a sweet low voice and was very warm-hearted.”

She told him that she was a countess, that her father had been exiled and the family had lost their property. She knew more about Scottish history than he did, and was very familiar with the story of Mary, Queen of Scots, whom she said she had portrayed in a tableau in Moscow.

“The attraction I felt for her ripened into real affection, and I offered to make her my wife if she would accept me. She replied that I had been a kind brother to her in her distress, but she could not marry me—she said, ‘I could not love you as I loved my old fiancé.’”

He arranged to meet her one night after she attended to some business, and was waiting for her in her hotel’s sitting room when the police arrived with the news that she had shot herself.

Her photograph was circulated to European authorities, and, within days, a note was received from F Stendahl, director of detectives, Stockholm: “Alma Teresia Bergstrom Ulfeld was a servant girl. Father labourer, poor, lives at Barsta farm, near Soedentelge. Cannot pay burial.”

A subsequent communication revealed further details. Teresa had been a lady’s maid with several families in Stockholm and had also been a waitress in a cafe in the old town—“During that time she several times expressed her disgust with life, and showed herself of a romantic disposition.” It said she had changed her name from Bergstrom to Ulfeld—adopting the name of the tragic 17th-century Countess Leonora Ulfeldt, revered for her loyalty to her disgraced but noble husband even beyond his death—only a few days before she took the boat to Scotland, dressed entirely in black.

The communication concluded: “The portrait which bears the name of Alexander Romanoff is that of a commercial clerk in this city, who casually made her acquaintance last summer and exchanged photographs with her.”

Teresa was buried without a headstone in the common ground at Seafield cemetery, in a coffin paid for by the Norwegian consul. A plate on the coffin lid read “Alma Teresia Ulfeld. Born 4th March 1877. Died 16th November 1897.”

1893—Catherine Hutton, 19, “an obstreperous Amazon”, according to the Evening News, who was fined £1 for beating James Murray with a poker and biting him on his wrist in the common stair.

1883—James Stewart, an ex-policeman who spent a lot of time in billiard halls, was “very much troubled by laziness” and was jailed for ten days for assaulting his wife and five children. In his defence, he said that his wife, Margaret, had so bad a temper that he “at least 200 times had to walk the streets of Edinburgh all night”, and she had attempted to commit suicide by taking laudanum, which would have left his children without a mother.

Popular brunch spot Edinburgh Larder currently occupies both ground-floor premises, but the first recorded business in the ground-floor-left shop, in January 1875, was a freak show displaying “ASTOUNDING NOVELTIES” including:

“The Great MAYO GIANT, weighing 41 stones 5 pounds, the Largest Human Being on earth, with MISS CAMPBELL, the Scotch Wonder, born without legs and with only one arm. Last, though not least, the EGYPTIAN MUMMY, the man that walked and talked 2000 years ago.”

Alma Ulfeld…. sad and fascinating in equal measure. Thank you for posting this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic stories from one Close, wonderful

David N

LikeLiked by 1 person

Careless lot living there. Falling down, drunk fighting, suicide.

I’d move out…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great stuff as always. So interesting seeing these nuggets about ordinary lives otherwise long forgotten. Great research. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Diarmid,

Hope all’s well. I love receiving these emails, they are so rich in history and in people. Historical people watching! Imagine you are asked this a lot. Have you considered making it into a podcast?

Thanks, Jess

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! A couple of podcasters have suggested teaming up — time is tight, but who knows?

LikeLike

Found this very interesting and informative. Particularly liked Catherine Hutton- an obstreperous Amazon-had a good laugh at that.Will visit the church in the Cowgate at some point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating and sad story of the ‘Countess’. Great work as always. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great stories, beautifully written as ever (laughed out loud at “Before long, all his professing led to her becoming pregnant”)

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a fabulous set of stories!! Best wishes June Professor June Andrews http://www.juneandrews.net http://www.juneandrews.net/

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

An ex cop “very much troubled by laziness”. Plus ca change, indeed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again, folks falling out windows! And of course lots of drunkenness. A fascinating read.

LikeLiked by 1 person