11 Dundonald Street, Edinburgh—a Georgian tenement, built around 1832, with six flats in the stair, over two main-door and two basement flats.

Former residents include:

1981—J Hutton, who wrote to The Scotsman to complain about traffic wardens: “It is quite incredible how many there are, often seen in pairs, one almost trips over them, they are almost a traffic hazard; one can play snap with them! It gives the capital a bad odour with visitors.”

1936—James Wallace Bell, founder of the Nameless Guild, a short-lived theatre company whose performers were, initially at least, anonymous—the gimmick was dropped before the end of the Guild’s year-long existence. Their final performance was an open-air staging of “A Winter’s Tale” in the university quad on South Bridge. The Scotsman praised James’s innovative direction, but regretted that the “steady drizzle of rain made attendance something of an ordeal.”

1926—William Davidson, who was speeding down Queensferry Road, drunk, when he saw a young man and woman cycling in the lane in front of him. He blew his horn and drove his car between them, knocking the woman off her bike. She was taken to hospital; he was fined £2.

1925—Peggy Meehan, a sixteen-year-old girl who left home on an August morning, bound for secretarial classes at Nelson’s college in Charlotte Square, but failed to return home. “To no one had she let fall the slightest hint that she had any intention of leaving her home.” It was very worrying.

Her mother could not think why Peggy would vanish without a word. She said Peggy had “a strong inclination to get work and thereby assist me financially”, as her husband, Peggy’s father, a merchant seaman, had drowned when his ship was blown up by a floating mine in 1919, since when money had been short.

Peggy’s dog, a Shetland collie, had disappeared a few days before she did, “and the girl was nearly brokenhearted over it.” Perhaps that had something to do with it? Nobody knew. She had been complaining of headaches lately, too. Was that relevant? No one could say.

Also: “She had an experience while we were on holiday that alarmed us. She went away one morning and did not turn up for her meals all day. She arrived home in the evening laden with wild flowers and told us she had fallen asleep and had not wakened till then.”

Further: “She was anxious to learn to dance, but I thought she was too young. We were discussing it one night with two ladies who were present, and one of them said she would not let anybody keep her from dancing if she wanted to. I wondered if that had had anything to do with her disappearance, and got a friend to go round all the dancing halls to see if she had been at any of them, but no one had seen her. I simply can’t think what has happened.”

After three weeks of fruitless searching, Mrs Meehan issued a public appeal for information, including a description of her missing daughter: “Peggy is 4ft 11in in height and has dark bobbed hair and large brown eyes. She has a dark but fresh complexion, with a faint burn mark on the underlip.” When she disappeared, she was wearing “a browny-grey tweed costume with patch-pockets and a semi-belt in front; a black hat, trimmed with Royal Blue ornaments; and a blue and white striped blouse with a Peter Pan collar and black ties.”

A week after the appeal went out, the manager of a Glasgow picture house told police that he had recently employed an usher answering the description of Peggy he’d seen in The Sunday Post. She had given the name of May Murray, but her insurance card bore the name Margaret Meehan.

Detectives questioned the girl in the cinema, determined her true identity, and returned her to her mother in Dundonald Street.

Peggy was nineteen when she finally left home, marrying Keith Scott, a business transfer agent. She divorced him in 1942 and, in 1946, married John Milne, a spirits merchant whom she divorced in 1953 before, in turn, marrying Dashwood Watt, a glassware salesman. She never had children.

Dashwood died in 1966, when Peggy was fifty-seven. She died in 1980, aged seventy-one.

1915—Maria Isbister, who moved to Edinburgh after the death of her husband, Robert, a general merchant in Shetland. Her daughters emigrated to Canada: Helen to Saskatchewan and Agnes to Manitoba, and her son George was “lost in a storm off the Siberian Coast”.

1912—William John Fairgrieve, a restaurant keeper and “hard working, respectable man who had not a great deal of leisure”, whose wife, Isabella, betrayed him with a cork merchant. Granting William a divorce, the judge noted that the evidence in the case had been “very unsavoury”.

1895—John Bennett, a commercial traveller who was stricken with a condition that prevented him from speaking but was refused aid by the Leith Commercial Travellers Benevolent Association because he had failed to declare that he had suffered a dangerous disease nine years before.

John’s health worsened—his condition was actually a series of small brain haemorrhages or strokes—and, completely unable to work, he went to stay with his mother in Pencaitland, where he died a few months later.

1869—John Ridland, a teenaged boy, who, while bathing at the Granton breakwater, “was seized with cramp and sank”. He was rescued by the son of the harbourmaster and taken to a nearby house, “where the usual remedies were applied for restoring him to animation.”

Two years later, John was arrested for dishonestly obtaining locks, fireirons and silverware from ironmongery warehouses by presenting them with forged order forms from a Princes Street shop, and was sentenced to twelve months’ imprisonment.

Three decades later, a John Ridland—almost certainly the same person—was appearing around town as a paranormal researcher, conducting experiments in telepathy and clairvoyance, which he dressed up with pseudoscientific blather about Hertzian waves. He raised funds for his research by hosting variety nights where he would perform “psychical and hypnotic demonstrations” on a bill including Highland dancers, character comedians, and “Bert Oswald, Popular Coon Vocalist”.

1840—Dr James Gloag, the mathematical master of Edinburgh Academy from 1824 to 1864, under whose tutorship James Clerk Maxwell first showed the aptitude in maths that was to make him Scotland’s greatest ever scientist, for which Gloag privately claimed much of the credit.

A former pupil of Gloag’s recalled his “real gift for teaching” combined with “certain humorous peculiarities of tone and manner”, which his pupils mimicked behind his back. Only one of his witticisms, dating from around 1845, has been recorded for posterity, as follows: “He once said to a nervous pupil who had crossed his legs and was sitting uneasily, “Ha, booy! Are ye making baskets wi your legs?”

Mystifying.

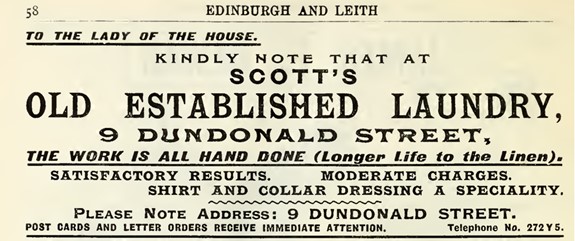

From 1895, and for much of the first half of the 20th century, number 9—the ground-floor-left flat—operated as a laundry.

The business was run by Mary Scott. Her husband, William, was a railway boiler cleaner. He died in 1943, of bronchitis. A few months later, their daughter Millicent died of tuberculosis, aged twenty-six. Mary sold the flat a few months before the end of the second world war. A quarter century later, Mary was living in a flat in Newington when, weakened by pneumonia, she fell and broke her neck. She was eighty-three.

The flat became home to Donald Nicolson, who, in 1951, was travelling through Corstorphine on the top deck of a zoo-bound tram when a fire broke out on the stairs. As smoke filled the tram, he smashed a window and passed several children down to the driver on the street below. However, it turned out there was no need for heroics. The fire (cause unexplained) was quickly put out by passing motorists using their “chemical extinguishers.” Some woodwork in the tram was damaged. Donald ended the day in the Royal Infirmary, being treated for cuts to his hands.

The ground-floor-right flat is number 13, whose former residents include:

Thomas Sellers (1920s), a drapery salesman, whose daughter Annie married a motor car driver and, a few years later, moved back into the flat when she was grievously ill with tuberculosis, and died there, aged thirty-one.

George Campbell (1910s), a miner, who got into a fight with another miner, Andrew Docherty, on a train waiting at Portobello station. In their struggles, a window was broken and the men were ejected from the carriage, and continued fighting on the platform. Both were fined 10s.

A weathered sign painted on a corner tenement reveals that the street was originally called Duncan Street, after Admiral Adam Duncan, the Dundonian naval hero of the French revolutionary wars. In 1885, to avoid confusion with Newington’s Duncan Street (named for the same admiral), the street was given a new name, commemorating Thomas Cochrane, 10th Earl of Dundonald, another hero of the same wars, though—as befits the elevated status of the New Town—a slightly more distinguished one.

Thank you for these lessons in specific social history… reading your accounts makes me happy!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love these people stories of bygone years, really fascinating. Thank you for sending these street stories to me, they brighten my day Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPad

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent as always, interesting lives of ordinary people, well told with great research. Thanks.

LikeLike

Fascinating – thanks so much for posting these stories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had to look it up and apparently crossing your legs used to be referred to as “having your legs in a basket.” Not sure why. Great post, as always, thank you!

LikeLike