4 Anchorfield, Newhaven, Edinburgh, whose current residents were evacuated (with an hour’s notice) on 23 January 2024, after building inspectors investigating cracks above a bay window determined that the tenement could collapse at any moment.

Former residents include:

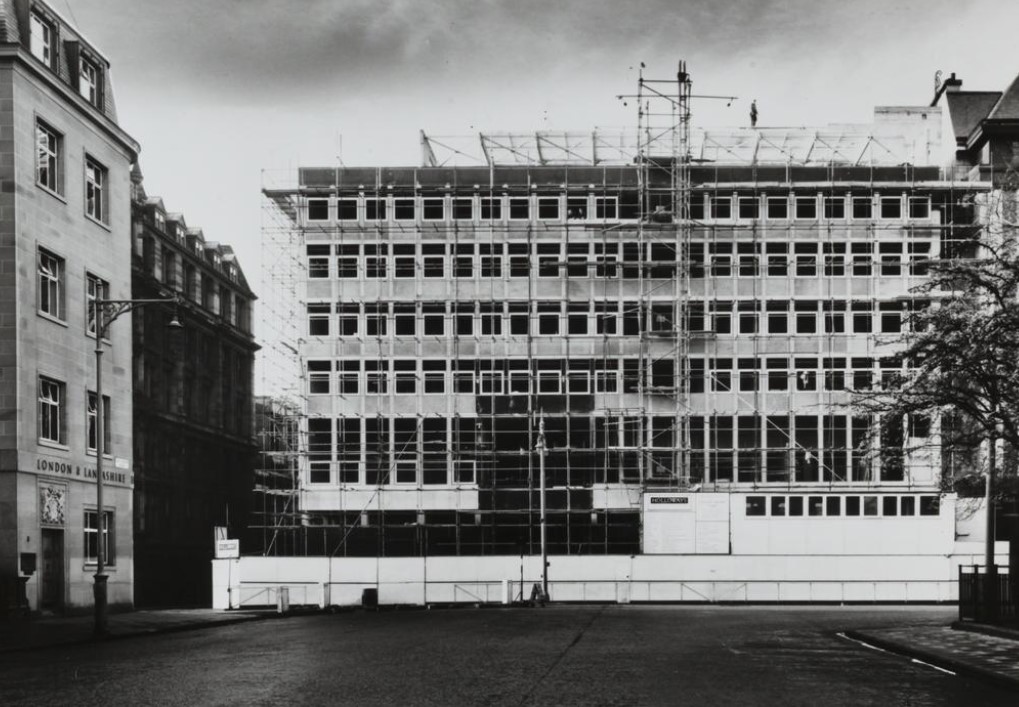

1961—Charles Airlie, a scaffolder, who survived falling down a lift shaft during the construction of the Basil Spence-designed Scottish Widows building on the corner of Rose Street and St Andrew Square.

1940—Elizabeth Lyle, a thirty-two-year-old air raid warden, who was on patrol when a German bomb hit a tenement at 8 George Street (now North Fort Street), just across the railway tracks from her home.

When she arrived at the scene, the building was in the process of collapsing. She broke a window to get inside and, as masonry fell around her, found a two-year-old child in a cot, “practically buried in debris.” She freed the child and passed it out through the window to neighbours before going back inside, where she discovered a badly injured man trapped under rubble. She stayed with him until she was ordered out of the building as the walls were about to cave in.

The man would have been David Duff, a basket maker, or Robert Thomson, a baker. Four women also died in the tenement: Lily Duff, (David’s sister), Catherine Helliwell, Catherine Fallon Baird and Catherine Redpath.

Although she had been injured by falling debris, Elizabeth assisted the rescue work all night, dressing wounds and helping find accommodation for residents of the destroyed tenement, until her divisional warden ordered her to go home and rest. A few months later, Elizabeth became the first person in Scotland to receive a royal commendation for acts of gallantry during an air raid. Tom Johnston MP, who gave her the certificate, said, “the child undoubtedly owes its life to her actions.”

Elizabeth died in 1991, at the age of eighty-three.

1939—Willie Flucker, mate on the Granton trawler Trinity NB, which was attacked by German fighter-bombers while fishing 80 miles or so off the Aberdeenshire coast. The planes dropped seven bombs, which blew the ship to pieces. The fireman, William Murray, was trapped and drowned. There was no time to lower the lifeboat, so the crew jumped overboard—all apart from the fireman, W S Murray, who was trapped belowdecks and drowned.

While the men clung to bits of wreckage, the planes returned, firing their machine guns. The cook, Bobby Wright, was shot in the leg and later died of blood loss and exposure.

After an hour in the freezing water, the men were picked up by a Danish schooner and taken to Norway. They returned home after burying Bobby Wright in Egersund kirkyard, alongside the remains of crew members of Royal Navy ships sunk by the Germans in 1916.

1935—Wilhelmina Flucker, who, shortly after 2 o’clock on a July morning in her seventy-first year, jumped out of a window of her top-floor flat, hitting the pavement with “a heavy thud” that woke her neighbours.

Her husband Robert—a trawlerman like their son, Willie, who would later almost drown in the North Sea when his boat was bombed by Nazi aeroplanes—died the following year of cancer of the tailbone, aged seventy-four.

Wilhelmina was almost certainly a Newhaven fishwife—Flucker was an extremely common name among local fishwives and fishermen, who were nearly all related by marriage (intermarriage with people outwith Newhaven being rare, and very much looked down on by the fishing community). The picture below shows one Barbara Flucker in the fishwife’s traditional working clothes, photographed by Hill and Adamson around twenty years before Wilhelmina’s birth.

Photograph (c) National Galleries of Scotland

The fishwives—who had since the 1700s traversed Edinburgh selling fish door-to-door from the creels they carried on their backs—had been viewed as a quaint anachronism since the mid-19th century, and their numbers were greatly reduced by the time of Wilhelmina’s suicide.

1929—Paul Slater, who, seeking a divorce from his estranged wife, Jane Small, asked a friend of his, a private investigator and former detective inspector named George Hall, to provide proof that Jane was having an affair. However, months passed and no such proof was forthcoming.

Eventually, Hall paid a handsome young man called Alexander Kane, with whom he had worked on similar cases, to use his wiles to one way or another endear himself to Jane in order that they might be discovered together in compromising circumstances.

After first presenting himself at Jane’s door in the guise of Alastair Macdonald, a charming insurance agent, Kane contrived to bump into her on the street time and again, offering to accompany her as she went about her business.

When he suggested one day that they take a tram to Craiglockhart for a walk in the country, she agreed. After they had walked awhile, they rested in the shade of some trees, whereupon, from out of nowhere, George Hall appeared, demanding to know what they were doing there.

Jane said she had done no wrong, which appeared to be true; the pair were simply sitting down at the side of the road in the middle of the afternoon. Nevertheless, Hall took their addresses—he and Kane pretended not to know each other—and told Jane she’d hear more of the matter.

Six weeks later, Paul brought divorce proceedings against her, citing the Craiglockhart incident as evidence of misconduct. The court was unimpressed by the flimsiness of the accusation, and the action was withdrawn.

Shortly after the hearing, Jane’s solicitors learned of the deception involving the fake insurance agent and Hall was charged with perjury, as, during the divorce hearing, he had of of course testified that the man he had seen with Jane was unknown to him. The jury unanimously found Hall guilty, and he was sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment.

1912—Maggie Mackay, who married Carl Thomesen, the son of a Danish shipmaster, and had two children, both of whom died—Carl, aged one, of convulsions, measles and rickets; and Ruth, aged five, of scarlet fever—before she herself died of tuberculosis at the age of forty.

1912—Albert Hone, an artillery regiment quartermaster. His marriage announcement in the Evening News proudly informed readers that his wife, Anna Robertson, was the “great-granddaughter of ANNA CATHERINE LYON or ANDERSON, O.P. Farm, Sunny Lack, Michigan”—whoever that might be.

Albert was killed in action in France on 25 April 1917, aged thirty-six. A year later, Anna married Frank Stemp, another quartermaster (in the merchant navy this time). There was no mention in the press of her Michigan ancestor.

1909—Minnie Flucker, who was the daughter of Wilhelmina Flucker, who would later throw herself from the window of her flat. Minnie died aged nine of meningitis caused by an infection of her middle ear.

1898—Isabella Flucker, another daughter of Wilhelmina Flucker. She died aged five months, when all her skin peeled off, layer after layer, and nobody could do anything to help.

The five-storey tenement was built in 1897 by James Campbell Irons, pictured below, a lawyer who supplemented his income through property speculation, financing the construction of tenements in Leith and Morningside.

Within two years of the completion of the Anchorfield block, two of Irons’ sons (one a partner in his law firm) died of inner-ear infections, and his sister drowned while swimming in the river Earn, near Crieff. Unbalanced by grief, Irons greatly overextended his investment in property speculations and, when a change in bank rates wiped out his already precarious profit margin, he was forced to file for bankruptcy.

In court, he struggled to hold back tears as he explained how the poor decisions he had made due to his “domestic trials” had left him “without a single penny in the world, depending on the generosity of friends for the subsistence of himself, his wife and family.”

A year later, his wife was found dead in a train at Portobello station, apparently having suffered a heart attack in her seat on the way from Waverley. Irons retired from public life, dying of a stroke ten years later, at the age of seventy.

Irons built the tenement on the site of Anchorfield House, a 17th or 18th-century mansion with a fine sea view. The picture below is perhaps the only surviving depiction of the house as it appeared before its demolition.

The image comes from a portrait of Sir Alexander Morison, a pioneer in the treatment of mental diseases, who was born in the house in 1779.

Image (c) National Galleries of Scotland

It was painted in 1852 by one of Morison’s patients, Richard Dadd, who was incarcerated in London’s Bethlehem hospital for the murder of his father, whom he believed to be the devil.

Dadd based his depiction of the house on a sketch by Morison’s daughter. The fishwives behind Morison are probably based on photographs by Hill and Adamson. Either—or each—of them may be an ancestor of Wilhelmina Flucker.

A lovely circular ending to the narrative there.

LikeLike

Fascinating! Thank you. Keep them coming, please!

LikeLike

Welcome back!

LikeLike

Thanks! Absence due to pneumonia, but I’m getting over it now.

LikeLike

Very interesting as always, thanks and keep up the great work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mother was brought up on the top floor of 34 N Junction Street. She remembers see the bomb leave the small aeroplane and heard the explosion of the bomb as it blew apart the tram lines on Prince Regent Street. Mum still remembers most the residents of her stair if you’d like to hear about them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Jamie. I’ve added 34 N Junction Street to the list of buildings to research.

LikeLike