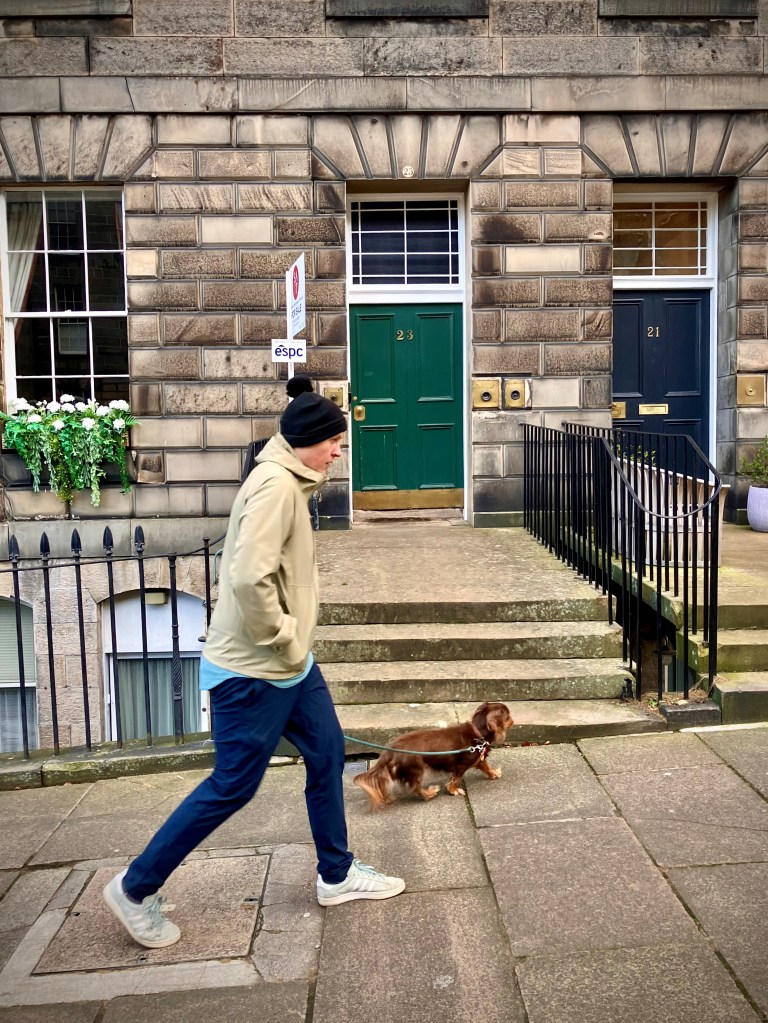

23 Scotland Street, built around 1823 on the northern fringe of the second New Town development. Three flats in the stair and one main-door property.

Former residents include:

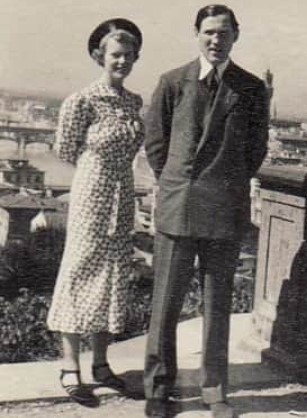

1952—Janet Henderson, the daughter of an architect, Thomas Andrew Millar, who died in the influenza pandemic that followed the first world war, when she was nine or ten. Her family were wealthy, and she entered adult life as a well-connected young debutante.

Between the wars, when she was in her twenties, Janet spent some time with her Uncle Bobby and his wife, Annie, in Vienna. Bobby was the son of Robert Whitehead, the inventor of the self-propelled torpedo, whose children had married into distinguished European families.

Bobby’s sister—Janet’s aunt—was Agathe Whitehead von Trapp, the mother of seven of the von Trapp children whose lives were dramatised in ‘The Sound of Music’ and who stayed with Bobby and Annie around the time that Janet did. Perhaps she met them. Perhaps they sang together.

Bobby and Annie introduced Janet to the “spiritual science” of the esotericist Rudolf Steiner and, when Janet returned to Scotland in 1937, she carried with her a belief in reincarnation, karma, clairvoyance and—importantly—vegetarianism.

She married a young East Lothian farmer, James Henderson whom she met playing tennis in Gullane. Under her guidance, he began growing organic vegetables in line with Steiner’s agricultural principles.

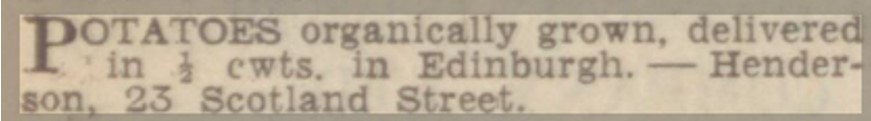

By the 1950s, they were living on the second floor of 23 Scotland Street. Their children—seven, like the von Trapps—attended the Edinburgh Steiner school (and, later in their education, Edinburgh Academy; the contrast must have been quite a shock), and Janet was delivering her organic vegetables to restaurants and shops, and selling them directly to neighbours.

(A former resident remembers that, at the time, “the street was a real mix of immigrants, bohemians, posh people a bit down on their luck” and “there was a very busy brothel next door.”)

In 1962, Janet opened a farm store at 94 Hanover street. The following year, she transformed it into Henderson’s Salad Bar, offering simple, inexpensive vegetarian food such as baked potatoes, cauliflower cheese, leek pies and mushroom savouries.

Henderson’s soon became an Edinburgh institution. The New York Times reviewed it, saying, “Anyone who spent any time on American campuses in the 60s will recognize Henderson’s as home: bright green and yellow walls, Beatles music blaring, bare wooden tables and straight-back booths.”

In 1974, the restaurant gained a mural, painted by Ken Wolverton, an American artist who had worked his passage to Scotland on a Greek freighter but, after a commission fell through, found that he was stuck in Edinburgh, being too poor to buy a ticket home.

His pay for the mural was one meal a day in the restaurant while he worked. He was finished in six months, but the free meals continued until 1983, when, he remembers, “for the first time I noticed it rained all the time,” and, having saved up enough money, he returned to America.

The year before the mural was commissioned, Janet became ill on a trip to south-east Asia and died after she came home, “refusing to be treated by doctors because of her belief in natural cures.” She was sixty.

Henderson’s went into liquidation in 2020, during the Covid pandemic. The following year, one of Janet’s grandsons opened a vegetarian restaurant in Bruntsfield under the Henderson’s name. I have eaten there. It is very good.

(The mural is now in Whigham’s Wine Cellars, which is owned by one of Janet’s sons. I have drunk there. It is also very good.)

Over the years, there have been reports of supernatural presences in Janet’s former flat. One of her granddaughters “always felt a malign presence in the house”, caused, she suspects but can’t be sure, by the calling up of spirits by mediums during Janet’s regular séances. “The final straw” she says, “was when my daughter was in a baby bouncer on the floor of the kitchen. I was in the hall and heard a really loud crash and went into the kitchen and a chair which had been a long way from her had landed centimetres from her head. Inexplicable.”

She left the flat that day, staying away for years until she arranged for a priest from the cathedral to bless the place with holy water. Her father, who lived there—one of Janet’s sons, who had become the wine buyer for Henderson’s—found the whole thing “a bit unusual.”

1951—Major Horace Frank Crossley Govan, a private in world war 1 and an officer (Gordon Highlanders) in world war 2, who became a church social worker, spending many years curing alcoholics through “spiritual treatment”. He was involved in the World-Wide Evangelistic Crusade, chairing meetings on subjects such as the ability of missionaries to cure “the absolute pagans and cannibals of the Congo” of the “utter selfishness of their lives” through exposure to the gospel.

1950—Alison MacCunn, the daughter of John Pettie, Victorian romantic painter. In 1889 in London, she married the composer Hamish MacCunn. He died of throat cancer in 1916 and Alison came home to Edinburgh, dying in her brother’s flat in Scotland Street 34 years later, aged 83.

1940—George, Catherine and Helen Imlay,three elderly unmarried siblings who had lived their whole lives in their flat on Scotland Street, which had been bought in the mid-19th century by their father, a fishmonger. The eldest, George, a printer, died in 1940 of a heart attack, at the age of 82. The following year, Catherine, a dressmaker, died of a stroke, aged 81. Helen, the youngest, an assistant in a jewellery shop, lived alone for two years, dying of emphysema in 1943, aged 76.

1936—William Alan Middleton, a young man who lived in the ground-floor flat, no.21, and was arrested one April night for what committing what the Evening News called an “Unusual Offence” in Buchanan Street, off Leith Walk.

A resident of Buchanan Street saw a stranger—William—loitering in the back green of his tenement and asked him what he was doing. “I’m only looking around,” he said, and the resident told him to be on his way. He went, but came back later, when he was seen by the same resident looking into a flat through its rear window. The resident chased him out of the back green but lost him in the street. William came back a third time, and was caught by the resident, who had been waiting in the shadows of the back green, and taken to the police station.

In court, the police testified that William had been sober when arrested, but William said, “I had a little too much to drink” and that his window peeping had been “the impulse of the moment.” The bailie said, “It is not a nice thing to do. One can only come to the conclusion that the policeman was wrong and you are right, for your action is inexplicable if you were not drunk.” He fined William £1. There is no record of any repeat offence.

1919—Richard J Porteous, an insurance clerk, who died at the age of sixty-eight with a weak heart, clogged arteries and inflamed kidneys. He had never married, and spent his evenings with his piano, harmonium and large library. His name endures in brass.

1887—Walter Wolston Ferguson, a 17-year-old member of the Phonetic Society and advocate of spelling reform, subscribing to Isaac Pitman’s arguments along these lines:

“The prezent mode ov English spelling haz been tried before the tribunal of reason and haz been kondemd. It has been kondemd by the unanimous vois of filolojists, who declare that it distorts the fakts, obstrukts the study, and hinderz the healthy growth ov the language.” And, further, it “defiez sciens, beliez history, obstrukts edukation, hamperz literature hinderz kommerz and cheks the growth of relijion and morality.”

Walter became a corporation cashier. His first wife died in 1924, of pneumonia, aged 56. Walter died of a heart attack in 1950, aged 80. His second wife lived for another four decades, dying at the age of 92 in 1991.

The name of his father, a master ironmonger, endures in brass.

1860—John Dickson, gun maker, who started his apprenticeship in gun making at the age of twelve, in 1806, and ran his own business in various Edinburgh locations from 1820.

The company’s best customer over its 200 years was an eccentric gentleman named Charles Gordon. Charles’s mother died just after he was born, and his father, an army officer, sent him to live with his aunt and uncle at Halmyre House, in the Borders. They, in turn, died when Charles was 14. He was left without parental oversight, with an inheritance including the Halmyre estate and a substantial income from it and other land. He is reported to have been “of unsound mind”, and soon began to burn through the large sums of money that had been left to him.

Between 1875 and 1906, Charles commissioned around 300 guns from Dickson’s, selling off valuable property including the Corstorphine Hill estate to fund his habit. Relations fearful that nothing would be left for them to inherit got a legal injunction to stop him buying any more.

John’s business is still trading, though its Edinburgh premises, on Frederick Street, closed in 2017.

His name endures in brass.

1854—Charles Black, founder, with his brother Adam, of A&C Black, publisher of the Waverley novels and the Encyclopedia Britannica throughout the 19th century.

Charles was troubled by a weak constitution. “For many years he considered that death had set its brand upon him” and, when people said he looked well, “he shook his head incredulously”, knowing them to be deluded. His poor health prevented him from being as successful as his brother, who rose to the posts of provost and MP for the city. When he died, one otherwise favourable obituary was forced to admit that “Mr C Black’s loss will not make a large blank in the community”.

1828—Miss Gregory, perhaps the first owner, who opened a boarding and day school for young ladies in the stair.

The first recorded crime in the street, which occurred in 1825, when some of the buildings were still under construction, was committed by a labourer by the name of Hall, who had previously served seven years in the hulks for a robbery in the house of Bishop Sandford.

He stole “immense quantities” of iron tools from the Scotland Street building sites where he was employed, climbed the scaffolding to strip the lead from the roofs and, “even ripped up the earth in the street to get to some lead pipes which were laid there.”

The next day, he noticed a policeman following him as he entered a broker’s shop in Blair Street. He ran off, discarding the tools as he went, but was caught. The Scotsman recorded his arrest, but not his sentence.

***

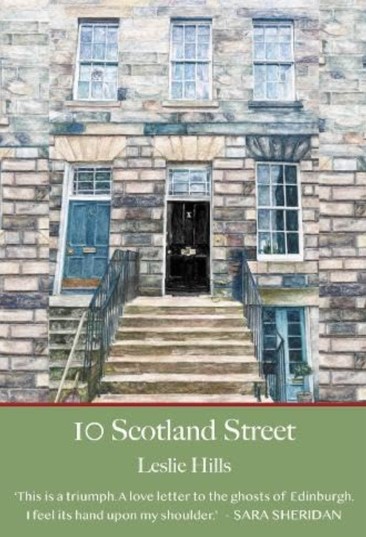

If you’d like a more in-depth look at another of the street’s tenements, I recommend Leslie Hills’ “10 Scotland Street”, which tells the story of “an Edinburgh home and its cast of booksellers, silk merchants, sailors, preachers, politicians, cholera and coincidence and its widespread connections over two centuries across the globe.”

If you like Tenement Town, there’s a good chance you’ll like this. It’s launching at Toppings on 1 December (https://www.toppingbooks.co.uk/events/edinburgh/leslie-hills-sara-sheridan-on-10-scotland-street-2023/) and is in bookshops now—just in time for Christmas…

A very enjoyable read, as allways. (There is one small typo: in the piece about Janet Handerson, you write “Henderson’s went into liquidation in 1920, during the Covid pandemic” – you mean 2020, I presume)

LikeLike

Thanks, Remco – edited!

LikeLike

Thank you, this address holds a lot of interesting history about the residents, especially the Henderson’s!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Policeman in 1825?

Robert Peel’s Law introducing police came in 1825, but no Police began until 1827 I thought?

Was this a policeman, or local security service? Very interesting.

Another very good tenement.

LikeLike

The article in the paper said a policeman followed him, so I guess there were polis on the streets back then. I just checked, and found this: “The Police Act of 1805 standardised the running of police forces to patrol Scotland’s burghs and led to the creation of a professional force in Edinburgh.”

LikeLike

That is very interesting. I never knew about the police act of 1805.

Peels came in 1825, and I am glad Scotland was way ahead of him.

Thanks for that.

Keep up the good work!

LikeLike

Excellent as ever Janet had quite the life ! Shame she didn’t allow the doctors to treat her !

LikeLike