248 Leith Walk, three storeys of flats over three shops. Built in 1902 as an investment by the owners of the nearby Victoria India Rubber Works.

1962—Andrew Curran, a docker who was unloading a cargo of sulphur from the MV Uranus at Imperial Dock when it caught fire. He was overcome by the noxious fumes and would have died if firemen hadn’t arrived to extinguish the blaze.

1957—Alexander Kerr, an excitable sixteen-year-old boy who travelled to west Edinburgh one Friday and, sometime after midnight, was arrested after residents of Slateford Road called the police to complain about the noise he and his friends were making. He was fined £10.

1956—Alfons Bociek, a young Polish refugee who got a job in the Victoria rubber works, married a woman named Isabella Smith, unofficially changed his second name to Bruce and became a naturalised citizen in his thirties.

1940—William Shade Leuchars, a radio operator in the merchant navy, who was reported missing after his boat, the SS Napier Star, was sunk off Iceland while carrying cargo from Liverpool to New Zealand. His body was never found. A year later, his father inserted a brief notice in The Scotsman to say he had been declared dead, closing with, “No letters, please.”

The U-boat that torpedoed William’s ship was captained by Joachim Schepke, known as “Ihrer Majestät bestaussehender Offizier” (Her Majesty’s best-looking officer). He died a few months after William, his U-boat damaged by depth charges and rammed by a destroyer when it surfaced.

1939—Alice Townsend, a seven-year-old girl who was playing on a slipway at the Seafield end of the Portobello promenade at high tide and fell into the water, which was about 8ft deep at the time. Her mother, Helen, jumped in to save her, but got into difficulties herself.

They were saved by a twenty-four-year-old man named Frank Frankowitz, from Craigmillar, who saw them struggling and jumped in after them, grabbing Alice and her mother and dragging them to the slipway, where three other men pulled them out.

Disappointingly, of Frank Frankowitz there is no further trace.

1916—Violet Sharp, a twenty-five-year-old woman who was working as a domestic servant in the mansion of Sir Arthur Pendarves Vivian, a Cornish industrialist and former Liberal MP, when she married Angus Murray, a corporal in the Seaforth Highlanders, and moved to Edinburgh. Eleven months later, Angus—who had, for some reason, been demoted to private by that time—was killed in the Somme.

1916—William Walker Paxton, a 50-year-old donkeyman (a nautical engineer in charge of the small engines that work winches, pumps and capstans), whose ship, the SS Astrologer, was carrying coal from Leith to France when it was sunk by a mine off Lowestoft. William was drowned, with ten other men.

The mine had been laid by a submarine commanded by Kurt Ramien, a bright young sailor who had joined the German navy as a cadet just eight years previously. After the war, he rose through the ranks, and became a government official in the Weimar Republic in his early forties. Then the Nazis came to power, and Kurt found himself serving something called the Third Reich. He left the government and returned to the navy as a rear admiral, taking charge of minesweeping operations.

Within hours of the declaration of war in 1939, a German submarine sank a British passenger ship, killing a hundred civilians. It seems Kurt understood this as a taste of things to come, and decided he wanted no part of it. Exactly a week later, he killed himself. He was fifty-one.

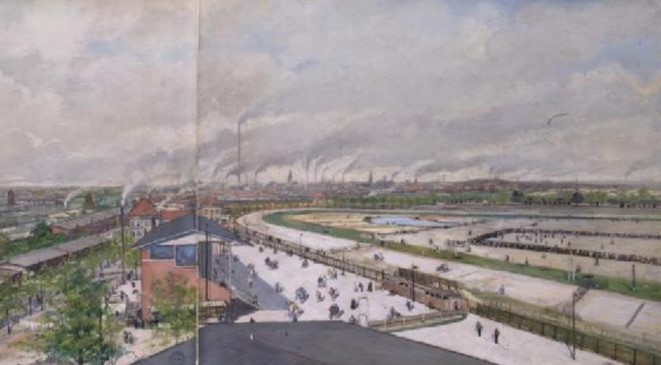

1914—John Milne, an engineer on a steamer that was docked in Hamburg when war was declared. He was arrested and interned in the Ruhleben civilian detention camp—an old racecourse on the outskirts of Berlin—for the next four years.

The camp housed around 5,000 men and developed into a small, self-run society, with its own police force, vegetable gardens, orchestras, football teams, and, as in Britain, a rigid class and race-based hierarchy. John could, no doubt, have found worse places to spend the war.

The stretch of Leith Walk where number 248 now stands was once known as Orchardfield, a collection of one and two-storey buildings backing on to a fruit tree nursery.

An iron foundry was built on the orchard in the 1860s, and a few years later the venerable dwellings were replaced by a three-storey tenement, which stood for only thirty years before being replaced in turn by the present building.

One resident of the vanished tenement was William Cochrane, a 67-year-old unemployed iron moulder who, in 1880, told his wife he was going for a walk, and whose respectably dressed but lifeless body was found washed up on the slipway at Seafield the next day.

Two other residents were Peter and Janet Rice, who ran a grocer’s on the ground floor, and sued Janet’s brother, Robert Jack—a draper in Liverpool—after he began sending them strange and rather menacing postcards and letters over the course of the summer of 1874.

One, addressed to “Skyn Flynt Rice” said: “Skin a flint in the giving and expect a fortune for the mere asking.” Another said: “Wha nailed the blankets and the sheets frae her helpless auld mither?” Yet another, slightly more coherent, said: “Thou wilt surely remit the £20 which thou owest me, and so thou wilt have an unsullied conscience to sell thy cabbages.”

The final straw was when Robert sent out cards to Peter and Janet’s friends, purporting to have been sent by Janet, with a message inviting them to Peter’s funeral.

Three years previously, on her wedding day, Robert had given Janet £20. She took it to be a gift, but now, after having become “addicted to drink”, Robert claimed that it had been a loan and demanded it back. Janet refused, which Robert thought was particularly unkind of her, as, following their father’s death, Janet, their sister and another brother had inherited £400 each, while Robert had been left absolutely nothing at all. Shortly after receiving Janet’s refusal, he began the campaign of harassment that led Peter and Janet to sue him.

To make up for the distress he had caused them with his letters and postcards and the “funereal practical joke”, the small debt court ordered Robert to pay Peter and Janet damages of £40. He did not.

Three months later, at the end of November, Peter and Janet were sitting in their kitchen at the rear of the shop around 11 at night when they heard someone enter by the shop’s front door. Janet went through and saw her brother standing at the counter.

He muttered something about provisions, but, by the way he was held his arm she knew he had something up his sleeve. She asked what he wanted. He didn’t answer, but lashed out at her, the straight razor in his hand slicing into her neck just under her jaw. She managed to call out, “Peter, come here; it’s Bob!” as Robert continued to attack her, slashing her hands as she tried to keep him away from her.

Peter ran in and knocked Robert into the partition wall. Janet, bleeding badly but quite alive (the razor had cut skin and muscle, not arteries or throat), grabbed him and together they wrestled him to the floor, assisted by a man—Alex Shaw, a cooper—who had been passing by.

Janet spent the next ten days in hospital, “and even after she came out her wounds were not healed.”

Robert—who, at his trial, “remained cool and collected during the whole time”—was found guilty of assault by cutting and stabbing, but not attempted murder, and was sentenced to seven years’ penal servitude. Perhaps it cured him of his addiction to drink. Or perhaps not.

Janet died of a heart attack, aged seventy-four, in 1917; Peter’s heart lasted a few years longer, giving out in 1924, when he was eighty.

Absolutely fascinating. Thanks Ann Burnett

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating stories as ever Thankyou !!

LikeLike

Fascinating stories as ever Thankyou !!

LikeLike

Another great instalment of Tennement Town! Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve decided some of these stories should be made into a series of short films called “Tenement Town.” They’re just fantastic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, very interesting. My great grandparents lived at this address in 1906. They were Olaf and Annie Levin.

LikeLiked by 1 person