3 Home Street—an early 19th-century tenement: nine flats over two shops facing the busy junction of Tollcross. Former residents include:

1954—Jean Robertson, a sixteen-year-old paper mill worker who moved into her aunt’s flat in the stair from her former home in Tron Square after her father murdered her mother, Betty, and brother, George.

Jean’s father, also George, was a forty-year-old bus driver. He had joined the Scots Guards as a boy, and later—when his children were infants—fought in the Spanish civil war with the International Brigades, where he’d lost a finger and had, in some unspecified way, “not been well.” An old antifascist comrade remembered him as “a drunkard and a lazy sort” but also “a braw soldier.”

Jean was one year old when her father came home from Spain, ten when her parents divorced after the second world war, and twelve when her mother married a ship’s rigger named James McGarry. That marriage didn’t last. Before long, McGarry was gone, and Robertson moved back in with the family. Jean was thirteen or fourteen by then, which it seems was when Robertson started molesting her.

In February 1954, Jean’s mother found out what he had been doing to her daughter for the past few years. She confronted Robertson, who, in a fury, screamed that he would kill her and the children with a hatchet. The police were called and he was removed from the house. He went to live in Carrick Knowe, in the west of the city, with his mother, who would later say that “he was choked with grief over whatever was wrong.” She didn’t know that he often went round to his old flat, banging on the door, frightening the family, threatening murder.

After a couple of weeks of this, on a Saturday night at the end of February, Robertson decided to bring it all to an end. He wrote a note on the back of a family photograph. It read: “How I will miss you all. To my dear mother, I can’t stay and tell you, but immaterial of what I may do or have done I love you with all my heart.” Also: “I can’t stick it any longer. The allegations and hurts I have had all my days from Liz are more than I can stand, as there is not even one item of truth.” He placed the photograph in the drawer of his dressing table and left the house—“in tears”, according to his mother.

Later that night, around 2 o’clock, Jean was awoken by her father’s voice. He was telling her mother to “go ben the kitchen.” Jean woke her brother and they went to see what was going on. Their father was in the hall. Before Jean could react, he had stuck a knife in George’s head. He then pushed her on to her bed, stabbing her in the stomach as she screamed for help.

A sound from the hall—her mother opening the front door—distracted Robertson, and he left the room. While he was gone, Jean tied some sheets together to make a rope and hung it from the window, but she was too badly wounded to use it.

When Robertson reappeared, he was carrying her mother over his shoulders. “There was a big hole in her stomach. Something white, which might have been a hankie, was round her mouth. Her hands were bound.” He threw her down in the kitchen beside the cooker. Then Robertson put tape round Jean’s mouth and tied her hands. He pulled off her underclothes but before he could go further, there was the sound of smashing glass, and Jean heard her brother outside, calling for help. Her father left her again.

George, though seriously wounded—perhaps fatally—had managed to go out of the flat and down the stairs to the ground-floor of the building, where their neighbours Larry and Kate Hay lived. He broke their kitchen window and climbed through it, collapsing on their kitchen floor. Larry and Kate came into the room as Robertson clambered through the window after George, a knife in each hand, and—too shocked to do anything—they watched as he stabbed the boy until he stopped moving.

Robertson looked up at the Hays “as if he was going to cry” and said, “That’s all through that woman lying up there, but she’s got what she deserves.” He asked Larry to help him lift George. Larry did, and Robertson carried his son out of the flat. He took him to Jean’s bedroom and placed him in a chair. He told Jean to get hot water, saying he would revive her mother and brother with whisky, and then went back to the Hays’ flat to ask for some bandages.

The Hays weren’t there—they had roused their children from their beds and gone to the police station on the High Street. (Other neighbours had heard screams but done nothing. One said, “It isn’t unusual to hear noises of that description at any hour in Tron Square.”)

The police found Betty lying dead where she had been dropped. George was sitting in the chair where he’d been placed, also lifeless. Jean was beside him, alive but bleeding badly, with an overcoat over her shoulders, her hands tied together with flex. Robertson was lying on the floor of the kitchen with his head in the oven, the gas turned full on. He was unconscious when they took him away.

Betty and George were buried in Mt Vernon cemetery the following week, a small group of mourners standing in the falling snow as their coffins were placed in the ground alongside the coffin of Betty’s brother, who had died in the war. Jean was still in hospital on the day of the funeral, but had recovered and gone to live with her aunt in Home Street by early spring, when she was able to lay flowers on the grave of her mother, brother and uncle.

She testified at the trial in June, which ended with her father being sentenced to death. He was hanged in Saughton prison at the end of the month—the last man to be executed in Edinburgh.

1953—Donald McLean, a barman who died of a heart attack after dinner one Thursday night. He was forty-four. A year later, his wife inserted an In Memoriam notice in the Evening News:

“Not just today but every day,

At sunset I remember,

And a voice whispers gently, ‘Kathleen.’”

His children, Donald, Alan and Doreen, added:

“We miss you, daddy, because we loved you.

A garland of beautiful memories will

always be entwined around your name.”

One evening, a few months later, a watch and fountain pen were stolen from one of the boys’ blazers as it hung in the changing room of Warrender baths. The notice asking for the return of the items said they were “of sentimental value.”

It seems likely that the watch and pen had belonged to the children’s father, meagre heirlooms that had perhaps gone by default to the oldest son, Donald Jr. There’s no way of knowing, but that’s certainly more likely than the possibility that the thief returned them.

1912—John Wallace, a seventeen-year-old plumber’s apprentice who stole bicycles left unlocked at the foot of common stairs and sold them cheap until he was caught and fined two guineas, with the alternative of 20 days’ imprisonment.

The next year, John’s friend Lauchlan Sinclair left a window unsnibbed in the fruiterer’s shop where he worked, by which means the boys broke in late one night and stole some small change and eight cakes of chocolate. The bailie said John seemed incorrigible and gave him a month in jail.

1909—Elizabeth Demeo, who was born in the tenement but lived there for less than a month before she was taken to live with an old couple in Montrose, distant friends or relations of the family. She spent the next few years of her life with them, never being told the reason why she was not with her parents. The old man was a drunkard, and they had hardly any money. She was dressed in rags and roamed the streets alone, barefoot and hungry, scrounging scraps to eat.

Just after she started school, the old man and woman died, within a week of each other, and Elizabeth was sent back to Edinburgh, where she was taken in by her mother’s sister, who lived in Dean village, on the western edge of the new town. Aunt Annie, a widow, resented the imposition as well as the difficulties that having to care for Elizabeth caused in her social life, which seemed to Elizabeth to revolve around carousing with the soldiers who flooded into Edinburgh during the war.

A gentleman visited Elizabeth every weekend—a tall man in a long black cloak, with cape attached. He told her to call him Papa, so she supposed that that was who he was. He was kind and gentle, and she liked that he slept beside her in her bed.

He told her something about why she couldn’t live with him or her mother, but she was too young to take it in or ask the right questions. She came to understand that a brother she had never met had had an accident and died, but she knew no more than that. For the time being, she was simply happy to have a papa at all. But then, without explanation, his visits stopped. One week he visited her as usual, and the next he failed to appear. She never saw him again. No one told her why.

Shortly after that, Aunt Nellie took Elizabeth to the Craiglockhart workhouse and left her there—again, with no explanation. The parish council sent her onward to the small village of Strathnairn, near Inverness, where she was left in the care of a woman called Barbara Fraser.

She stayed there for seven years. “Auntie Barbara”, as she was told to call the lady, gave her a good home—“happy and memorable days” in “peaceful harmony”, the house resembling “a fairy enchanted cottage” on moonlit nights. These were the happiest years of Elizabeth’s life. However, when she turned fourteen, the money that the parish council in Edinburgh was paying Auntie Barbara stopped and she had to move on.

Over the next few years, Elizabeth worked as a housemaid for a succession of wealthy Inverness-shire families, but the question of her strange childhood troubled her. In July 1931, at the age of twenty-two, she handed in her notice and travelled to Edinburgh to look for answers.

Aunt Annie was still living in Dean village. Elizabeth told her she wanted to know what had happened to her family. Why had she been sent away? Was her papa alive? And her mother? From what Annie told her, and from other sources over the years to come, Elizabeth was able to piece together the awful events surrounding her abandonment. She learned that, in the year preceding Elizabeth’s birth, her mother had lost not one but three children.

In April 1908, three-year-old Catherine had died of measles; in August of that year, nine-month-old Gladys had wasted away from digestive failure; and in March 1909—twelve days before Elizabeth was born—her brother, Frances, had been murdered.

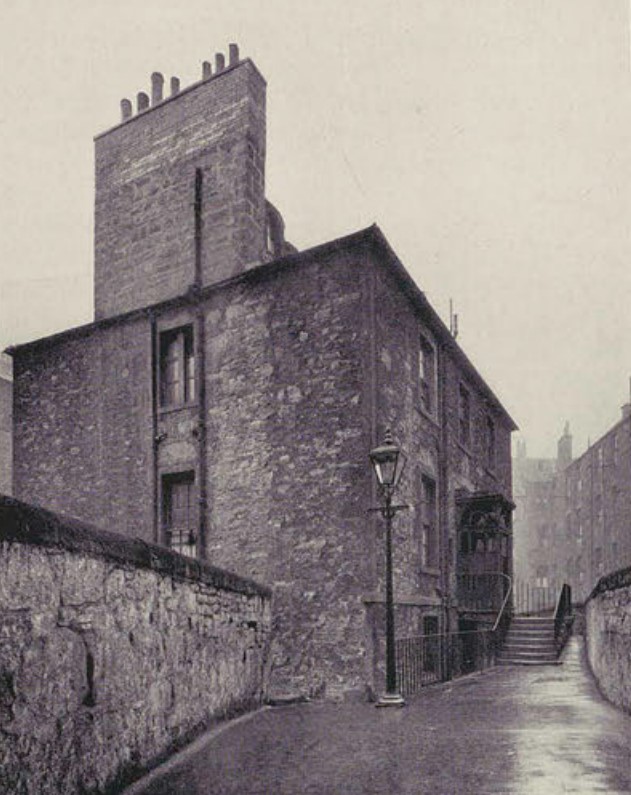

He was playing outside the tenement (on the left of the picture below) when an Irish labourer, John O’Neil, picked him up and threw him down the steps of the Tollcross underground lavatory (in the middle of the junction, by the clock). His head split open on the bottom step.

O’Neil was insane, hallucinating. He told police, “I saw my brother with his legs and arms and head cut off, and a procession walking round about him, and it was time that I was doing something.” He was imprisoned as a criminal lunatic, probably for the rest of his life.

Frances, unconscious, was taken to the infirmary in a cab. His mother was told what had happened and hurried along Lauriston Place as best she could in her advanced state of pregnancy. He died a few minutes after she reached him.

On the day of Frances’s funeral, five days later, thousands gathered in the street, blocking the traffic. The Scotsman said: “A sudden hush came over the great crowd as the little white coffin was carried out and placed in the hearse, the men in the crowd uncovering their heads.”

Elizabeth was born the following week. Her mother was a wreck. She couldn’t bear to see the child. She refused to nurse her. She said she’d kill her if she had to look at her. Philip Demeo—Elizabeth’s father, according to the birth certificate, although her mother said she’d had no personal contact with him in almost two years—couldn’t or wouldn’t take her, so a home had been found for her with the old couple in Montrose.

Annie told Elizabeth her papa was dead but her mother was alive. She said, though, that her mother was no good, and it would be better if she stayed away from her. Elizabeth didn’t listen.

She tracked down her mother, who was managing a boarding house in Portobello. There were tears, mostly on Elizabeth’s part, and when her mother invited her to stay with her to see if they could make up for the past, she accepted. There followed a summer that Ellizabeth would later describe as “a taste of paradise”. However, the taste was soon to sour.

In September, Elizabeth’s mother seemed—for some unspoken reason—to grow cold towards her. Elizabeth became uncomfortable in the house. Feeling that her mother perhaps saw her as a burden, she began to avoid her, creeping away, trying not to take up space. Then, one night, her mother flew into an inexplicable but terribly violent fury, threatening her with a kitchen knife, beating her and kicking her when she fell to the floor. Elizabeth grabbed her possessions and fled into the night, homeless, penniless and alone.

She found a job in a convent, where she remained for some years in what seems to have been a state of severe depression until, hearing that Auntie Barbara in Strathnairn was ill, she went north to care for her. After less than a year, Auntie Barbara died from a stroke. Elizabeth more or less immediately suffered a nervous breakdown.

The next few years saw her in and out of work, in and out of workhouses, convalescent homes and hospitals. Her mental state worsened. She was overcome by paranoia, unable to accept help because of an irrational but overwhelming fear that the aid would turn into a trap. When she was placed in some sort of locked-door institution in Edinburgh—she didn’t know its name or its exact purpose—she escaped by climbing over the wall and tumbling down a wooded slope. On another occasion, believing herself to be in danger of being locked in a room in a homeless shelter on Edinburgh’s High Street, she climbed out of a third-floor window, clinging to a ledge until a woman in the next tenement leaned out of her window to pull her in. Later, after being taken to a girls’ shelter on Dean Terrace, she escaped through an upstairs window and broke into the top floor of the next door house after climbing over the balcony.

Eventually, she ended up homeless and starving in Sussex, where she had gone to ask for shelter at a convent and been turned away. The convent put her in touch with a welfare worker, who got her a job as a table maid in the home of the director of a London bank. She stayed long enough only to save enough money to buy a ticket on a boat back to Scotland.

In Aberdeen, she took a series of brief domestic jobs until she found stability as a companion to a retired teacher. When, in 1942, the woman died, she left Elizabeth her villa and a good sum of money. Elizabeth sold the house and rented a modest flat in a tenement.

In 1955, Elizabeth moved to Inverness—apparently retired from service at the age of forty-six. Now going by the name Suzie McKay (McKay was her mother’s maiden name) and dressed in her habitual uniform of plastic overcoat, wellington boots and black beret with a McKay clan crest, she became a well-known character in the city, where she devoted herself to raising money for charity, and had distributed tens of thousands of pounds to good causes by the time she died, in October 1998, at the age of eighty-nine.

1907—Alexander Logan, son of a comb maker, who went to work as a butler in the University Club on Princes Street when he was twenty-five. He worked there for a quarter of a century, until he died of an intestinal obstruction at the age of fifty-one.

1902—Frank Bodden, who was born in the tenement. He grew up to be a electrician and joined the air force at the start of the second world war. He was troubled by gall stones for two years, and died in 1941, aged thirty-nine, of post-operative shock after he went to hospital to have them removed.

Victorian locals knew the shop on the left as Mr Young’s Auction Rooms, where they bought whole hams, cheese, tea, washing powder, polishing paste and other home necessities “in quantities to suit small families.”

Twentieth-century locals knew the premises on the right as a jeweller’s shop belonging to Jack Levey—during the second world war, the greatest amateur billiards player in Scotland—who promised “first-class prices for second-hand jewels” and sold diamond rings for as little as £5: “DIAMOND RINGS—A LIFELONG INVESTMENT, CERTAINLY, WHEN BOUGHT FROM JACK LEVEY!”

And Georgian locals knew the area as the fruit tree nursery in the northern part of the grounds of Drumdryan House, a mansion just outside Edinburgh proper, belonging to the family of Home Rigg of Tarvit, who sold it at the end of the 18th century, when the opening of Lothian Road made the area a prime site for the construction of a dense residential district.

The mansion survived—subdivided into flats and in an increasingly forlorn state—in the back greens of the tenements that lined the new streets that were laid out around it, overlooked by the kitchen and bedroom windows of the working class, until it was demolished in 1959.

I remember Suzie aka “Sexy Suzie”.

She was always chasing men with her brolly around Inverness when she was in town.

Shop floor would clear when word got about she was in the shop. She cottoned on that we were avoiding her in the store room, so she’s walk in and would chase us about with her brolly.

Not satisfied until she jabbed one if us in the bum with it.

I remember her as an eccentric little old lady. Never knew of the heartbreak she went through growing up.

She was well known back in the day and is still fondly remembered.

She wrote a book called “A Discarded Brat A Tiny’s Tale of Survival” by Elizabeth ( Suzie) McKay.

LikeLike

That’s brilliant! I bought a second-hand copy of her book (which is where the details in the story above come from). Odd that she doesn’t mention her umbrella antics!

LikeLike

I lived in Home Street and a woman was murdered in number 3 one new year. I think it was 1999. Two men threw her over the balcony 🙁 so many tragic stories.

LikeLike

I didn’t know about that. Another tragic connection to the building, in that case.

LikeLike

Fascinating! I was going to ask how you had found out about Elisabeth’s tragic early life and beyond, but that’s answered in previous posts. I guess the events around the double murders of Betty and George were reported in the newspapers of the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I learned about Elizabeth/Suzie’s life from the memoir she published in 1980, “A Discarded Brat”. It’s quite eccentrically written but vivid and full of interesting details of the life of someone who we would not otherwise know anything about. In the preface, she writes: “In writing my autobiography, I felt as if I were speaking to someone and unburdening myself to a friend. It has, somehow, given be great relief and I have not been so lonely.” Everything else in the post, like most of the things on the website, comes from old newspaper reports.

LikeLike

Fantastic reading !!

LikeLike